Pour la version française de cet article, veuillez cliquez ici.

Para leer este artículo en español, haga clic aquí.

The townspeople’s terror and anguish was palpable.1 The gunshots and armed conflict had been going on for more than a day and a night when the first cylinder bomb exploded at 10:30 a.m. It was May 2, 2002. The day before, the leftist guerilla group known as the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC-EP) had attacked the far-right paramilitary group United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia (AUC) in the town of Bojayá. Both illegal armed groups had been fighting for control over this territory coveted for its wealth of natural resources and the routes it provided for the illicit trafficking of arms and drugs.

Bojayá is found in the Department of Chocó, on Colombia’s northern Pacific coast. The population is largely indigenous and Afro-Colombian. The region has a long history of human rights violations and extreme poverty along with suffering abandonment by the Colombian government.

The Catholic Church has also been present in Bojayá for centuries. Perhaps for this reason on this particular day, in the midst of the armed combat and explosions, about 1,500 townspeople decided to seek refuge in the Catholic church building, in the priest’s home, and among the Augustine nuns.

At 10:45 a.m., the third cylinder bomb torpedoed through the church roof and exploded on the altar, killing 119 people and wounding 98. Children and whole families had been sheltering there. The explosion also destroyed the arms and legs of the church’s Christ on the Cross, leaving only the torso intact.

Throughout Colombia, this image of the mutilated Christ became a symbol of the 2002 massacre in Bojayá. Years after, during the peace negotiations between the FARC and the Colombian government in 2015, leaders of the FARC visited the community of Bojayá and asked the families of the victims for forgiveness. Amazingly, when Colombia voted in the plebiscite on the peace agreement that had been hammered out between the government and the FARC, 96 percent of the people in Bojayá voted in favor of making peace. In contrast, a slight majority of the country—and especially a strong majority of Evangelical, Pentecostal, and charismatic churches—voted against the accords. The result was a national rejection of the peace accord. Shortly after, however, the accords were renegotiated and then signed in November of 2016.

What does this story have to do with the Mission of God and Global Partnerships? I suggest that the massacre in Bojayá and the plebiscite that followed can provide us with important historical lessons about Catholic and Evangelical/Pentecostal missions in Colombia. Extracting such lessons from a specific context like this Colombian one and its past will be very instructive in guiding our future mission efforts.

First of all, I want to clarify some concepts I believe to be of paramount importance before going into detail about lessons that we can learn from this story.

-

Mission

By the term mission, I refer to what the church is and does to bear witness to Jesus Christ in her ministry of reconciliation. Let me expand this definition a bit further:

What the church is:

- The church is a foretaste of the reign of God.

- The church does not “have” a message; it is the message.

- The church as message refers to its presence. This means any mission that is not communal and interdependent is weak.

- The presence of the church brings with it the proclamation of the gospel of Jesus Christ through both word and deed, thus promoting reconciliation.

According to Genesis 12:1–3, the divine plan for blessing all the nations on earth is achieved through the creation of a new community. This new community will live out a new relational ethic and will be the key in showing other nations the will of God for humanity. Hence, the mission of God requires a new community that practices a new way of relating (ethic) within a new order of reality. In the Scriptures, this new way of relating implies relationships rooted in justice, peace, and equality (cultural, economic, gender; see Gal 3:28). Practicing this new ethic will act as a centripetal force that will attract other nations of the Earth to want to know God. As such, the mission of God requires a new people with a new countercultural and alternative ethic that displays different political and social values from those commonly espoused in the context where this new people is to be found (Sermon on the Mount; Luke 4:16ff; etc.).

This understanding of God’s mission stands in sharp contrast to the concepts inspired by a poor interpretation of Evangelical Pietistic thought, that place emphasis on (1) mission carried out by individuals who understand salvation as personal and (2) a new life for the individual that will culminate in eternal life to be personally enjoyed after death.

According to evangelical theologians Brad Harper and Paul Metzger, however, the church’s identity “is itself communal and relational. It derives this communal being from the Triune God whose being is the three divine persons in communion, and who created it for communion.”2 This communal and relational identity must reflect the kind of unity that we see in the Trinity. It is in the communion of the church—love, self-denial, forgiveness, and service—that the world can see the communion and character of God. This is a reason why divisions, lack of trust, fights for power, and authoritarianism are a scandal and contradiction to our witness to Christ.

This brings us to the definition of another term of utmost importance for today’s reflection—that of partnerships.

-

Partnerships

Our societies desperately need alternatives to violence and resentment. People yearn to see palpable examples of reconciliation, love, and forgiveness. The nations of the world long to see communities where nationalisms are overcome, where love is the mark of relationships, where forgiveness is a regular practice, and where reconciliation is a lived reality—together viscerally and visibly demonstrating the God we believe in. Only these kinds of communities will have the right to be heard in contexts of suffering where people are searching for new paradigms of peace and justice. In the words of Catholic theologian Gerhard Lohfink, “The real being of Christ can be bright only if the church makes visible the messianic alternative and the new eschatological creation that happens from Christ.”3

For this reason, we need to avoid the specialization and fragmentation that is typical of modernity and move to practical and relational experiences of holistic ministries that honor specialization without falling into separation. “We look forward to the day when our coming, common hope—the Lord Jesus—will make us one. We must live today in view of that day,”4 say Harper and Metzger. We do not need to wait until the second coming of Christ to experience communion and unity. Furthermore, we are called to live as a new creation in order to serve in the ministry of reconciliation. This ministry requires a community that lives now in light of what will be. Otherwise, continue Harper and Metzger, “we will continue sending a very clear message to the surrounding, cynical world that our God’s gospel is powerless to break down divisions among his people.”5 It follows that “partnership is not just a good suggestion” but God’s mandate for the church—God’s redeemed and reconciled community—affirms Jon Lewis,6 former president and CEO of Partners International, a nonprofit Christian ministry.

Therefore, “partnerships” is the term I use to refer to the kind of relationship that can be found among the people of God when we serve together interdependently in the mission of God. Partnerships require a solid relationship and a shared purpose that fosters joint plans and the sharing of resources. Partnerships play a fundamental role in God’s reconciling mission when we take seriously John Driver’s interpretation of God’s reign. Driver, a Mennonite theologian and international teacher, says God’s reign is made manifest through the concrete forms that life takes on among God’s people, and it is precisely in the midst of the relationships between them that the perfect Kingdom becomes a reality.7 In fact, according to Andrew Walls, British historian of missions, “The very height of Christ’s full stature is reached only by the coming together of the different cultural entities into the body of Christ. Only ‘together,’ not on our own, can we reach his full stature.”8 Therefore, multicultural partnerships are at the center of God’s mission.

Some years ago in the context of this Council of International Anabaptist Ministries meeting, I mentioned the call to understand mission—in addition to reconciliation, evangelism, and service—as God’s activity of bringing together diverse social fragments as parts of the same body, bringing to reality what Paul describes as the “very height of Christ’s full stature.”9 Ugandan Catholic priest and theologian Emmanuel Katongole names this call an “Ephesian Moment.” According to Ephesians, the “aha” moment of reaching the full stature of Christ happens when we are one with people of different cultures, serving and enriching each other. In this multicultural environment, we see the complete image of Christ.

With these two concepts in mind—mission and partnership—we return to the Colombian context to learn from experiences of missions there. After that, we will look at lessons from the African and European contexts in order to propose some possibilities for the future.

Lessons from the Past

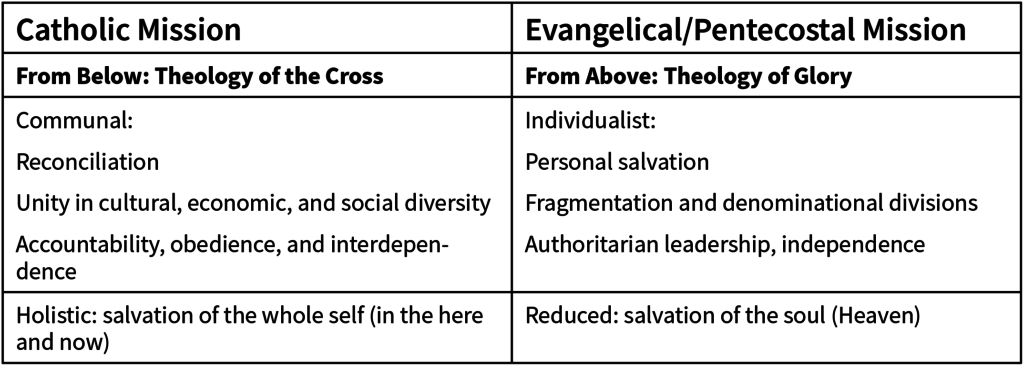

Catholic and Orthodox missions made the expansion of Christianity possible during its first 1500 years. Even though this expansion was often embedded in armed empire expansion, aggression, and conquest, it is of utmost importance to learn from these missions given the short mission history of the Anabaptist movement. In the specific Colombian case of the Bojayá massacre, the Catholic community’s response to the plebiscite on the peace accords is very interesting in comparison with the response of the churches that are the fruit of Evangelical/Pentecostal missions. Taking into account what I mentioned above that both the method and the means are the message, the following table demonstrates some of the differences in mission methodology. Clearly this is a generalization; there are, of course, nuances and exceptions in the different missions of each tradition.

According to Latin American theologian and missiologist Samuel Escobar, “The traditional Catholic missionary orders such as Franciscans or Jesuits, which are supranational, provide the oldest and more developed example [of cooperative models], facilitated by the vows of poverty, celibacy, and obedience.”10 We commonly find in these mission models monastic orders that opposed structural systems based on exploiting the poor, and that preached a Gospel of vulnerability where Jesus identified with the needy and shared their suffering. The shattered crucifix of Bojayá is a clear image of God incarnate who is with the poor, experiences their reality, and suffers with them.

In contrast to this model, many non-Catholic missions arrived in Latin America from a position of power and wealth. Cases abound where the missionaries serving among the poor chose to live in housing separated from the people they served. The empty cross spoke of a God of Glory, distant and unmoved, who related to some groups in terms of doctrine while offering others economic prosperity. This model tended to import not only theologies from North America but also the liturgical, musical, and church organization styles from there. Sadly, the message’s contextualization was minimal.

Having been sent in community, the monastic orders communicated a message of interdependence, cooperative service that required obedience and mutual submission, conflict resolution, forgiveness, and reconciliation. In this model, salvation was dependent upon a community. The Catholic orders tangibly showed that people of different nationalities, economic classes, and social standing could live and serve together thanks to the Spirit of God. On the other hand, Evangelical/Pentecostal missions, preaching a gospel of personal and individual salvation, left community life on a secondary plane. In their fragmentation and competitiveness, some agencies promoted the message that independent service was possible, that obedience was not necessary, and that division was a valid option when faced with disagreement.

Lastly, Catholic missions were not separated by type of mission or service. Although some monastic orders specialized in specific ministries, within the orders they had a variety of tasks related to education, community development, and caring for the sick. They thus developed and practiced holistic missions. In contrast, North American missiological differences resulted in some agencies placing the proclamation of their individualist gospel ahead of service and made saving the soul more important than attending to immediate and contextual needs.

The missiological method of the Catholic missions in Latin America communicates a concrete message, as does the Evangelical/Pentecostal missionary method. This could perhaps explain why many non-Catholic churches in Latin America ended up adopting the culture of the “empire”11—understood as individualism, materialism and consumerism, and authoritarian leadership. The rejection of the peace process, along with the explicit political alignment of the evangelical churches with the far right in Colombia, is strong evidence of this reality. A God of Glory who does not identify with the poor, who demands retributive justice, whose salvation is solely personal with implications for life after death only, and who supports the ministry of authoritarian leaders who submit to no one, is a very different God from the shattered Christ of Bojayá.

Praise God that in our Anabaptist tradition we are able to find many examples of mission in solidarity with the people, rooted in community, and holistic at its core. For reasons of brevity, I will only mention two of these examples.

-

The Kenya Mennonite Church (KMC)

The Kenya Mennonite Church (KMC) is a result of the work of the Holy Spirit in a revival in the Tanzania Mennonite Church in 1942 when the first Mennonite preachers arrived in Kenya from Tanzania. It was an African-to-African church growth movement that started in rural areas of western Kenya and later moved to small towns. It was characterized by experiences of miracles and healings. In addition, it dealt with tribal and cultural differences and with tensions among people of different social classes and levels of education.

The work of the Holy Spirit brought unity, interdependency, and trust among God’s people. Bishop Philip Okeyo from the KMC says, “When trust is developed between partners in mission, great speed of accomplishment is guaranteed.”12 This summarizes very well the work of the international agencies that joined the KMC in its effort to bring a holistic gospel to Kenya. Missionaries from Eastern Mennonite Missions (EMM) accompanied relief and development work led by Mennonite Central Committee (MCC) along with support for business entrepreneurs by Mennonite Economic Development Associates (MEDA).

Now after 75 years (1942–2017), the Mennonite church in Kenya, the fruit of a Tanzanian church mission, comprises 12,000 members in 145 congregations and has planted a new church in Uganda that in turn became a member of Mennonite World Conference (MWC) in 2017.

This missiological model, with its strong emphasis on the gifts of the Spirit and its clear Anabaptist-Pentecostal identity, is a critique of modern movements of revival that offer prosperity without renouncement, power without humility, salvation without following, and joy without self-denial. In the church mission from Tanzania to Kenya and then from Kenya to Uganda, we see a mission model from the ground up where Christ crucified is both the strategy and the message, and where dependence on the Holy Spirit leads to ministries of justice, peace, and reconciliation. We are reminded that the New Testament gospel of salvation comes to us from a position of socioeconomic and political weakness rather than from economic affluence and human power.13 As described by Anabaptist missiologist David A. Shank,14 the missionary attitude must be defined through Christology by:

a) Self-denial, as a pre-requisite;

b) Service, as its position;

c) Identification, as the risk;

d) Humble obedience, as contradiction;

e) The Cross, in consequence.

-

The Ministry Partnership between French and North American Mennonites

According to David Neufeld, “From 1953 to 2003, MMF [Mission Mennonite Française] and MBMC (Mennonite Board of Missions after 1971) worked with each other and with a variety of other partners, most prominently Mennonite Central Committee (MCC), to develop a joint missionary venture . . . [that resulted in] the founding of three Mennonite congregations in the greater Paris area, the establishment of ministries for youth with developmental disabilities and mental health conditions, the development of ministries for foreign students and for people with social and spiritual needs, and the creation of a center for the study and promotion of Anabaptist theology.”15 Allen Koop, cited by Neufeld, observes in his study of postwar evangelical missions in France that “no other missionary project in the country during the latter half of the twentieth century fostered cooperation as close and as productive as that carried out by French and North American Mennonites. No other mission succeeded in combining evangelism and church planting with significant social work to the same degree. No other mission demonstrated the same openness to collaborating with outside groups and agencies, including the French state.”16

This model demonstrates the opportunity that joint projects represent for bringing distant groups together and inviting them to work together. It requires interdependence during the planning, evaluation, and completion of the project, which is in and of itself a mark of a healthy partnership.

In addition, this experience reveals the importance of strong organizational structures that help to clarify roles, facilitate communication, and formalize accountability processes. The effect of donors and the source of funds needed to sustain a mission would be another instructive topic to explore in this history, especially considering that Catholic missionary practice is to have a common purse in managing mission funds.

Possibilities for the Future

Theology, ecclesiology, and missiology must be developed by taking the final goal into account. God calls us to live the truth, a new creation that reflects God’s intention for the world. Eschatology, therefore, is the beginning of missiology.

Thus, Mennonite World Conference (MWC) wishes to ask ourselves what God’s intention is for God’s people and then build our global church structure and mission practice from there. It is this vision that propels us to promote interdependent work among the agencies related to our member churches. At MWC, we would like to see enhanced relationships and cooperation among our approximately 75 mission agencies, 50 service agencies, 30 agencies working for justice and peace, 140 health organizations, and 130 educational institutions. Even so, we have encountered the following obstacles:

- Some agencies from the Northern hemisphere prefer to think of MWC as an event where we meet to tell stories. The idea that we can be a global communion that plans and works together on concrete projects is a little scary for some.

- Some agencies from the Northern hemisphere privilege efficiency over interdependence. The latter slows everything down, in their view, and needs a lot of patience.

- Some agencies compete with one another. The need for economic support and donors leads them to highlight their own work and diminish what others are doing.

- Some agencies lack a theology and understanding of what the church and the global communion are. It is not clear to them why a global church is necessary; this makes a multicultural interdependent mission difficult. For these agencies, God’s reign is limited to individual local congregations and independent agencies that don’t need to be in fellowship with others.

- Some leaders continue to put their goal of increasing numbers ahead of Anabaptist convictions and relationships within our communion.

- Some leaders are unaware of and devalue what their predecessors decided. They aim to start their ministries from scratch, ignoring what others have built in and contributed to the churches and ministries that they now aspire to lead.

Given the above, I want to insist on the necessity of dialoguing with our Catholic monastic roots. Monasticism influenced our Anabaptist movement at its inception.17 Genuinely learning from their vow of poverty can help us propose a mission that promotes living simply as some of our Anabaptist agencies already do. In the words of Escobar:

Before any “practical” training for mission in the use of methods and tools for the verbal communication of a message, it is imperative to form disciples for a new style of missionary presence. Mission requires orthopraxis as well as orthodoxy. . . . This Christological model that was also the pattern under which Paul and the other apostles placed their own missionary practice could be described as “mission from below.”18

By the same token, a look at their vow of monastic obedience could help us avoid the sin of division that we Anabaptists have so easily fallen into over the centuries. The Global South in particular needs new models of leadership that know how to submit one to another in humility and not accept fragmentation as something normal in the life of the church. God’s intention for humanity invites us to send mission teams, or “micro-communities,” that include members from different cultures; practice lifestyles matching that of the people they seek to serve; mix evangelism with peacebuilding, community development, attending to the sick and education; and practice forgiveness and reconciliation. This is the only way we will succeed in being the message that God has for God’s creation.

It is my prayer that the Christ of Bojayá continue to call God’s church to the sacrificial mission of service to the neediest, to a mission that results in faith communities that practice daily forgiveness and reconciliation in the living hope of a new creation.

Footnotes

César Garcia is General Secretary of Mennonite World Conference.

Brad Harper and Paul Louis Metzger, Exploring Ecclesiology: An Evangelical and Ecumenical Introduction (Grand Rapids, MI: Brazos, 2009), 19.

Gerhard Lohfink, La iglesia que Jesús quería: Dimensión comunitaria de la fe cristiana, 4a. ed. (Bilbao: Desclée de Brouwer, 1986), 191–92.

Harper and Metzger, Exploring Ecclesiology, 35.

Harper and Metzger, 281.

Jon Lewis, “Servant Partnership: The Key to Success in Cross-Cultural Ministry Relationships,” in Shared Strength: Exploring Cross-Cultural Christian Partnerships, eds. Beth Birmingham and Scott C. Todd (Colorado Springs, CO: Compassion, 2010), 59.

John Driver, “The Kingdom of God: Goal of Messianic Mission,” in The Transfiguration of Mission: Biblical, Theological, and Historical Foundations, ed. Wilbert R. Shenk (Scottdale, PA: Herald, 1993), 86.

Andrew F. Walls, The Cross-Cultural Process in Christian History: Studies in the Transmission and Appropriation of Faith (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis, 2002), 77.

Emmanuel Katongole, “Mission and the Ephesian Moment of World Christianity: Pilgrimages of Pain and Hope and the Economics of Eating Together” Mission Studies 29, no. 2 (2012): 183–200.

Samuel Escobar, “The Global Scenario at the Turn of the Century,” in Global Missiology for the 21st Century: The Iguassu Dialogue, ed. William David Taylor (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2000), 34.

René Padilla cited by Milton Acosta in “Power Pentecostalisms: The ‘non-Catholic’ Latin American church is going full steam ahead—but are we on the right track?” Christianity Today (July 29, 2009), https://www.christianitytoday.com/ct/2009/august/11.40.html.

Philip E. Okeyo, “A Word from Kenya,” in Forward in Faith: History of the Kenya Mennonite Church; A Seventy-Year Journey, 1942–2012, eds. Francis S. Ojwang and David W. Shenk (Nairobi, Kenya: Kenya Mennonite Church, 2015), 8.

John Driver, “Messianic Evangelization,” 200.

David A. Shank and James R. Krabill, Mission from the Margins: Selected Writings from the Life and Ministry of David A. Shank (Elkhart, IN: Institute of Mennonite Studies, 2010), 159–67.

David Yoder Neufeld, Common Witness: A Story of Ministry Partnership between French and North American Mennonites, 1953–2003 (Elkhart, IN: Institute of Mennonite Studies, 2016), vii.

Neufeld, 154.

C. Arnold Snyder, Following in the Footsteps of Christ: The Anabaptist Tradition, Traditions of Christian Spirituality (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis, 2004), 27.

Escobar, “The Global Scenario at the Turn of the Century,” in Global Missiology for the 21st Century: The Iguassu Dialogue, ed. William David Taylor (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2000), 43