(Para la version original en español, haga clic aquí.)

Introduction1

In this essay we will examine Matthew 9:35–38 in order to uncover some of Jesus’s missiological principles. These principles should serve as a guide for the church today, so that it might carry out its mission from a more biblical and Christological perspective. The world demands of us a “conversion on the way,” that we rediscover Jesus of Nazareth in the challenges brought to us by the concrete needs of the people and take heart in Spirit’s renewal.

Characteristics of Jesus’s Missiology

Jesus’s missiology was centrifugal, local, and peripheral

We begin by remarking on three characteristics that emerge from Matthew 9:35a. Jesus’s actions were oriented outwards. The text says that Jesus traveled around all the villages and cities. He did not wait for people to come to him; although at times people’s needs required him to do so, this was not the norm of his earthly ministry. He did not barricade himself within the temple of the great city, gathering the multitudes for some “conference for the attainment of spiritual power.” Jesus was where the people were. It is impossible to respond to people with the gospel when we are ignorant of their entire situation, for example, of their housing situation, their history, or the problems they face. Often our proclamation of the gospel is irrelevant because of its form, not its content. William Reyburn, writing on the theme of missionary identification, tells the story of when he began to eat with the Kaka of Cameroon. “An empty bowl of larva,” he wrote, “is far more convincing than all the empty metaphors of love that so many missionaries are prone to employ with pagans.”2

Another mission group that works with indigenous people in Argentina developed a philosophy of ministry in which the missionary is understood as a “guest.”3 The missionary from this perspective must only go upon receiving an invitation, and then must listen, wait, and share.

A related story involves foreign missionaries being surprised to find that a local missionary who worked with various ethnic groups from his own country spoke eight languages. They asked him how he had achieved such a feat, expecting him to share about an advanced linguistic strategy. His response: “I just went where the people were.”4

The villages Jesus traveled around were all in Galilee. Jesus began his ministry in his own region, Jerusalem, and Samaria—forgotten and despised regions of Israel. This choice of location is indicative of Jesus’s theological perspective. The fact that he attended to the marginalized masses, the poor and excluded, expresses a divine intention—theses historical dimensions of Jesus’s life were not incidental to his ministry. Orlando Costas says, “It is enormously significant that Jesus chose Galilee—a racial and cultural crossroads—as his mission base.”5 Other social classes, of course, need the gospel; but Jesus’s imparted a missiology rooted theologically in the needy, the poor, and those isolated from official systems.

Jesus’s missiology was continuous with prior work and was dialogical

Jesus went to the existing institutions of his time, Jewish synagogues, and did not establish alternative educational centers down the road. To an important extent, Jesus did not bring a strange teaching but rather proposed a renewal of existing teaching from within. He was an expert on Jewish beliefs and, granted that he grew up Jewish, his thorough knowledge of Judaism gives us a clue for missiology today: we must take seriously the beliefs of those people among whom we do mission work, immersing ourselves in their meanings and symbolisms, and refusing superficial attitudes and a priori condemnations. We must understand that the various cultures cannot break totally with their histories or worldviews. The gospel, it is true, is transformational and there are certainly conflicts in theory and practice; but the good news of the Reign of God is more redemptive than condemnatory. Hesselgrave says, “The missionary can provisionally adopt the worldview of his nonbelieving hearers and reformulate the message from their point of view, so that it would be meaningful.”6

Although this attitude is not an easy one to adopt, and it is perhaps impossible to do so completely, the effort to understand the other is worthwhile. Such understanding enables the gospel to become something new within the mental structures of its hearers. For an animist group to hear the Holy Spirit is not the same as for a Western culture. The missiologist Charles Kraft says, “We not only need dynamically equivalent translations of the Bible, but also a dynamically equivalent evangelization that translates events, religious practices, normative systems, etc.”7 In this way, the gospel does not produce a cultural vacuum, but rather what anthropologists call “functional substitutes.”8 For example, communal celebrations were common among some indigenous cultures in the Americas; these celebrations reinforced intra- and inter-clan relations, and fomented artistic expression and group solidarity, among other things. A vacuum is created if, when Christianity arrives, the natives or missionaries decide to put an end to the festivities. Cultural harmony is ruptured. Such a rupture is avoided if Christian festivals, including their dances and songs, etc., replace the functions of the earlier ones.

When Jesus came to the Jews claiming to be the Messiah, they understood quite well what he was talking about. Jesus, as the Lamb of God, was comprehensible within the Jewish sacrificial system. To a certain extent, Jesus reinterpreted the tradition of the people among whom he worked as a missionary. We must understand that God does not arrive to a people with the arrival of the missionary; instead, God has long earlier been involved with that people. Jesus’s missiology was accordingly dialogical: he did not claim to annul the law, but rather to fulfill it. “The term used for ‘fulfillment’ is plerosai, which means ‘to complete in its fullness,’ which implies progress; it is not to maintain something in the same state as it was previously.”9 The fact that Jesus could say, “You have heard it said” (Matthew 5:21–48), means he was thoroughly familiar with the theological history of the people. Paul likewise affirms in his message to the audience at Listra that, although God permitted each nation to walk in its own ways, this does not mean they were left without testimony of him. Paul had learned well from his teacher. He further demonstrates his learning in his dialogue with the Athenians, which shows that he also knew Greek thought well. Examining Acts 17:22–34 we observe the following features in this dialogue:

Paul begins the dialogue affirming the Athenians’ religious attitude. He does not begin by censuring all that they thought; instead he lauds their historical theological developments.

He initiates the dialogue from the starting point of his hearers’ psycho-socio-spiritual reality. He had paused to look at their altars. We might say that he had taken off his shoes on the Athenians’ holy ground.

In an intelligent and redemptive move, Paul refocuses the Athenians’ adoration of the unknown God, arguing strategically that he knows this god. God will take the place of their gods. Theological continuity emerges here, as well as the necessity of reformulation.

Then Paul began to proclaim the word, just as Matthew shows Jesus teaching and preaching. Paul recovers the positive dimensions of some native philosophical proverbs, using them to reinforce a new theological truth.

Jesus’s missiology was liberating

Matthew 9 says that Jesus healed every sickness and disease. In Jesus’s time, Jews had the firm belief that “illnesses were caused by the sick person’s own sins or by demons.”10 “The New Testament considers illness to be contrary to God’s intentions at creation, sees demonic power in it, and draws a general connection between sin and illness.”11 Given this wider meaning of illness for first-century Jews, healing represented far more than physical restoration: it vindicated the whole person, physical, social, and spiritual. Belief in retribution was common in Jewish thought, and sin and sickness were viewed as closely related; sickness was an evil that affected the entire person. Forgiveness and healing were, similarly, as going hand-in-hand.

The Greek words used by New Testament authors for sickness and disease are malakia and nosos. “Malakia is related to fragility, weakness, and illness. The word only occurs in Matthew 4:23, 9:35, and 10:1.”12 A medical dictionary says “malakia means softness, weakness, impotency.”13 “Nosos is related to the Latin term nocere, which means ‘to hurt,’ ‘to injure,’ and from there ‘sickness.'”14 We can see that both words indicate an undesirable state that involves the influence of external factors. That state includes sickness and pain, biological and emotional symptoms, and physical and social incapacitations. Jesus bursts in to this situation with his power that breaks the vicious circle of marginalization and isolation. For instance, in Mathew 11:22–29 Jesus shows that his ministry inaugurates a new era, a ministry that “binds the strong man” and brings liberation. Jesus’s healings are evidence that the reign of darkness has begun to fall. As Boff observes, “Matthew presents Jesus to us as a New Moses. The messiah will bring a paradigm of liberation, just as Moses did, and this paradigm is characterized by signs and wonders. Jesus is the new liberator of the Hebrew people.”15

Jesus’s missiology involved identifying with others

Jesus’s motivation for identifying with the sick, hurting, afflicted, and exhausted, those mistreated by life’s circumstances and those who did not seem worthy of living, flowed from his compassion. Jesus was moved by compassion, but it was not external circumstances that shaped his desire to act to eradicate the causes of those circumstances. Rather, it was his internal virtue, cultivated through a spirituality in tune with God’s love. Jesus removed his friends’ sandals in order to truly comprehend their lives and to be able to feel their daily vicissitudes.

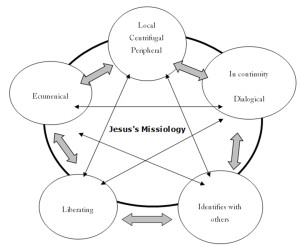

All of the aspects of Jesus’s missiology work together and are interrelated. He visited villages, dialogued, and taught because he identified himself with those he met; he healed and brought new life through his compassion, and this same compassion led him to invite others to join him in eradicating the evils that destroy [despellejan] human life. The virtues of Jesus’s missiology do not, therefore, only work sequentially, but they affect one another mutually and organically. We can represent this graphically in the following manner:

Jesus’s missiology was ecumenical

Jesus had no intention of carrying out the work by himself. He lacked even the slightest desire to impose a monolithic vanguard over and against other movements. At a certain point the disciples encounter unknown persons casting out demons; this generates distrust and jealousy among the disciples, because the others were not part of Jesus’s intimate group (Mark 9:38–41; Luke 9:49–50). They inform Jesus, hoping for a response in line with their expectations, but Jesus replies otherwise. For Jesus, others had truth and it was legitimate for them to perform good works; they belonged to his “macro” group. He gave no place to his disciples’ narrow exclusivism. In Matthew 9, Jesus tells the disciples to pray that God would send workers. There was a place for others, with their different gifts and ways of acting. They shared the same objective, God’s Reign in the midst of diversity and plurality.

Conclusion

This essay is not exhaustive, but it does illuminate part of Jesus’s missiology. Once again Jesus of Nazareth challenges Christianity and puts himself forward as the inescapable model of our faith practice. Let us follow him.

Footnotes

José Luis Oyanfguren is a missionary among the indigenous Toba Qom people of the Argentine Chaco. He works with the Mennonite church of Bragado, Argentina, and Mennonite Mission Network.

The essay was translated by Jamie Pitts, co-editor of Anabaptist Witness and Assistant Professor of Anabaptist Studies at Anabaptist Mennonite Biblical Seminary.

William Reyburn, “La identificación en la terea misionera,” in Misión Mundial: un análisis del movimiento cristiano mundial, vol. 3, Consideraciones transculturales, 2d ed., ed. Jonatán P. Lewis (Miami: Editorial Unilit, 1990), 23.

Willis Horst, Ute Müller Eckhardt, and Frank Paul, Misión sin conquista: acompañamiento de comunidades indígenas autóctonas como práctica misionera alternativa (Buenos Aires: Ediciones Kairos, 98). See Willis Horst, Ute Paul, and Frank Paul, Mission without Conquest: An Alternative Missionary Practice (Carlisle: Langham, 2015).

Gastón Salamanca, Adquisición de segunda lengua (Lima: SIL, 2004), 36.

Orlando Costas, quoted in Samuel Escobar, De la misión a la teología (Buenos Aires: Ediciones Kairos, 1998), 39.

David Hesselgrave, “La cosmovisión y la contextualización,” in Misión Mundial: un análisis del movimiento cristiano mundial, vol. 3, Consideraciones transculturales, 2d ed., ed. Jonatán P. Lewis (Miami: Editorial Unilit, 1990), 102.

Charles Kraft, El cristianismo desde una perspectiva transcultural: un estudio sobre teología bíblica dinámica (Mexico: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1981), 165. See Kraft, Christianity in Culture: A Study in Dynamic Biblical Theologizing in Cross-Cultural Perspective (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis, 1979).

Wilmar Stahl, Culturas en interacción: una anthropología vivida en el Chaco paraguayo (Asunción: Editorial El Lector, 2007), 27.

Francisco Lacueva, Curso de formación teológica evangélica, vol. 10, Ética cristiana (Barcelona: Editorial CLIE, 1989), 77.

Fred H. Wright, Usos y costumbres de las tierras bíblicas (Grand Rapids, MI: Editorial Portavoz, 1981), 149.

Gerhard Kittel and Gerhard Friedrich with Geoffrey W. Bromiley, Compendio del diccionario teológico del Nuevo Testamento (Grand Rapids, MI: Ediciones Desafío, 2003), 505.

W. E. Vine, Diccionario expositivo de palabras de la Biblia (Miami: Editorial Caribe, 2003), 294).

Clínica Universidad de Navarro, Diccionario medico, http://www.cun.es/diccionario-medico.

Vine, Diccionario expositivo, 317.

Leonardo Boff, Jesucristo el liberador: ensayo de Cristología crítica para nuestro tiempo (Santander: Editorial Sal Terrae, 1985), 138.