In this reflective article I will introduce you to the Taiwanese Mennonite medical missions era of the 1950s–70s, focusing on my grandparents’ deep involvement in that era and detailing some of its expressions in our family. I will then share how memories of my grandparents and their ongoing legacy in my own journey as a nurse gave me courage to continue nursing during the COVID-19 pandemic. I will tell you something of those difficult pandemic memories and share a piece of art I made in response to that time, explaining its significance to me and my journey as a pandemic nurse. In closing, I will reflect on the implications of medicine, mission, and faith as a nurse who follows Christ.

What I have to offer in missiology or theology for medical crisis is more practical than theoretical, coming through my family heritage and direct experience of the COVID-19 pandemic as a frontline registered nurse. During that time, I was caught up in a great storm and did my best to move through it with what courage and grace I could muster. For me, Mennonite medical missions had a unique role in that mustering. I hope you find some meaning in these stories1 along with some considerations of what medical mission might mean in all its multifaceted, beautiful confusion.

Taiwan Mennonite Medical Missions: 1950s–1970s

The Birth of Mennonite Christian Hospital (MCH)

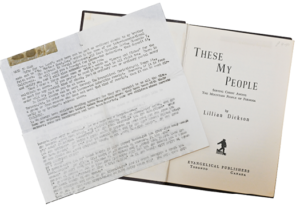

One of the first missionaries in post-war Taiwan was a Presbyterian American named Lillian Dickson. She published a book titled These My People2 about missions among the Indigenous Austronesian peoples of the Taiwanese mountains. While some of her vocabulary and language feel socially and politically dated in our current times, her account of Christian witness is nevertheless adventure-filled and moving. Dickson writes, “In 1946 . . . they needed everything after the war. They needed food, they needed medicine, they needed clothing. They only asked for one thing, ‘Are there any Bibles in America?’”3

As the workload in Taiwanese missions mounted, Dickson and her husband asked Mennonite Central Committee (MCC) to join alongside the projects Presbyterians had started; our family copy of Dickson’s book has a typewritten financial support request letter still tucked inside the front cover, possibly from Dickson herself. In the 1950s, MCC began to send contingents of missionaries, doctors, nurses, and administrators to these underserved Indigenous populations in the remotest areas of Taiwan.4 In 1954, Dr. Roland Brown founded a hospital that became central to the story of my family—Mennonite Christian Hospital (MCH) in the city of Hualien.5 There MCC staff trained Indigenous locals to be nurses, dentists, and public health specialists.6 Grandma Ruby Friesen (then Ruby Wang), the daughter of a local chief, was one of those trained at the nursing school. After graduation, she began her nursing career in mobile clinics and the MCH neonatal ward.

Grandpa and Grandma Friesen Join the Taiwan Medical Missions Work

Around 1957 or 1958, Grandpa Alvin Friesen moved from Canada to Taiwan to serve as a physician in the MCC mobile clinics and obstetrical/gynecological care at MCH,7 where he became the primary obstetrician. Grandma must have caught the eye and attention of this young Mennonite doctor, as she describes him coming to spend time on the neonatal ward with her even after his duties were done for the day. Mennonite archival records show Grandpa and Grandma spending time together outside of the hospital as well; photographs depict Alvin and Ruby as young adults posing for various projects—in particular, the mobile clinics.8

The mobile clinics must have added quite the adventure to my grandparents’ relationship. Grandma describes packing medical supplies into repurposed army vans (the medical missions version of Anabaptists turning swords into ploughshares, as it were), driving them out as far as there were roads, and then carrying the heavy supplies on their backs the rest of the way to remote mountain villages. In a similar vein, Dickson writes, “Whenever our Medical Mobile Unit starts out for the mountains, we know that adventure lies ahead, adventure with a capital ‘A.’”9 The photos of these mobile clinic vehicles—being driven rather intrepidly through the jungle on what can barely constitute roads, and crossing swollen rivers—seems to bear this out.10 Upon arrival at each village, Grandpa and Grandma sometimes saw more than one hundred patients a day.

In 1961, Grandpa and Grandma were married. Their choice of each other for lifelong partnership defied many social conventions at the time, since interracial marriages were extremely uncommon and not usually approved by the couples’ families. Of significance was the relationship my grandparents formed with Dr. Brown11 and his wife, Sophie, who became close family friends and colleagues. Over the years, the children of the two couples grew up together. On my side of the family, that included my father, Han Friesen (named after Han Vandenberg, another Taiwan Mennonite missionary12) and his siblings—my Auntie Heidi and my late Uncle Peter.

For Dad and his family, medical missions life was just ordinary life.13 Much of what I know about MCH comes from family stories from those years. Additional significant information comes from a three-volume bilingual Chinese-English historical account published to commemorate the hospital’s sixtieth anniversary. This work is something of a family treasure for us. In 2008 Grandma and Auntie Heidi traveled to Hualien for its presentation and other sixtieth anniversary celebrations; Grandpa had passed away in 1995, and MCH wanted some of his family members present since part of the sixtieth anniversary involved dedicating a new obstetrical ward to his name.14

Pioneering Public Health and Social Equity

MCC was committed to serving people with the poorest and lowest social status, and in post-war Taiwan this was undoubtedly the mountain Indigenous peoples.15 As an outgrowth of that commitment, Mennonite medical missions in Taiwan in the 1950s through the 1970s were pioneering concepts of public health and social equity, likely before the words were invented academically.16

In those days, infrastructure was limited and expensive between the east of Taiwan, with its Indigenous population, and the more affluent west of Taiwan, with its burgeoning immigrant Chinese population. Indigenous peoples had been forced into structural poverty due to multiple mechanisms of politics and colonialism.17 They could not afford to travel to city hospitals on the west side for their healthcare or to pay the medical bills charged by those hospitals.18

A story involving Grandpa illustrates this challenge. According to Dad, a close nurse colleague of Grandma needed emergency surgery but was unable to make a trip to the large city hospital in Taipei. And Dr. Brown, a surgeon of some skill, was not available. So Grandpa read from a textbook on the needed surgery, then literally brought the textbook into the operating theater with him and performed the operation. When my family visited Taiwan in 2016, this nurse was still healthy and delighted to meet us.

MCH was also innovative for its time in providing training for local Indigenous populations to serve their own people.19 The training helped people reconnect with one another. Grandma was a living example of this. Because she grew up during the Japanese occupation,20 she was forbidden to speak her own traditional language in school and had never learned it properly. She told me it was not until she started serving fellow Indigenous patients as a nurse with MCH that she really began learning her own language.

Through unique partnerships between Mennonites, Indigenous locals, and Chinese-Taiwanese locals, these missions helped Indigenous peoples move toward health equity, or what could perhaps be termed health justice. Not only were immediate health needs served but Indigenous peoples and other locals were empowered to take charge of their own healthcare. To return power to the patient so that people have agency over their own health is now one of my own personal goals as a nurse, in part inspired by the work of my grandparents and Dr. Brown.

Reflections While Becoming a Nurse

As a teen in 2010 I remember my family visiting the MCH obstetrical ward, which was dedicated to Grandpa.21 We were treated as honored guests and given a tour of the entire hospital. It was very disorienting to have a picture taken with much pomp and circumstance in front of a gigantic, larger-than-life image of my grandfather. I felt both proud of his achievements and undeserving of the honor bestowed upon us by subsequent generations of MCH staff—unearned, in our case, but offered for Grandpa’s sake.

Grandpa was a very self-effacing person, and, from what people have said about him, my guess is he would be embarrassed if he knew such an honor had been given him posthumously. But people recognized and wished to commemorate Grandpa’s undeniable love and passion for his Indigenous patients. Dr. Brown, for instance, describes the day that “Typhoon Winnie hit. It blew off part of the hospital roof. . . . Dr. Friesen, who lived two blocks away and was concerned for the patients, crawled on hands and knees to get to the hospital because of the strong wind.”22

Grandpa left an enduring legacy after his death, and both my grandparents seem to have started a new vocational trend in our family. Previously, generations of Friesens and Wangs had simply continued farming like their grandfathers before them. After Grandpa and Grandma, however, Dad became a doctor, Auntie Heidi became an occupational therapist, and I became a registered nurse.

In my young adult life in nursing school, I used to tell my classmates about Grandpa and joke that the rest of us never measured up to him. It was not really a joke, however; the feeling of not measuring up did not dissipate after I started my registered nurse career in a busy hospital on the Canadian prairies. How could I feel like I was a meaningful healthcare professional as a little floor nurse in some random hospital when my grandfather had been such a visionary, with obstetrical wards named after him and special recognition from Taiwanese dignitaries?23 I worked hard to begin my career but felt distinctly like an average, rather than exemplary, nurse. I could perhaps write more about how proud I am of Grandpa’s legacy and how it inspires me in my own healthcare career to continue with his same passion and dedication. However, “not measuring up” is the more honest description of how I experience carrying his legacy. For me, commemoration of Grandpa’s medical work is a complex mixture of pride in his accomplishments and worry about personal inadequacy on my part—that I may not be capable of the heights he achieved.

The ’Rona

Fast forward to March of 2020. When the ’Rona hit, as we nicknamed coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 in the small rural ICU I was working in at the time, nursing practice became unrecognizable almost overnight. In the “first wave,” everything was an unknown—how contagious the virus was, exactly how it spread, and how to care for people who caught it.

Our healthcare team was slowly crushed under the weight of additional equipment and interventions needed to care for patients on the heightened isolation precautions required for COVID-19. We began running out of everything we needed: hand sanitizer, protective gowns, medical masks, gloves, eye goggles, and sanitizing wipes. We were mandated to ration, and sometimes reuse, our personal protective equipment (PPE). Some days we did not know where our next shipment of gowns or gloves was going to come from. Our ICU only had one negative pressure room and needed several more for the “aerosol-generating procedures” much covered but poorly described by the media. So our maintenance department cut holes in the window glass of the ICU rooms and installed makeshift negative pressure machines.

Hospitals everywhere struggled to keep up with the scant and constantly changing available evidence about how to manage this virus. Each morning I would read our hospital policy updates, and by each afternoon they were already obsolete. This made providing care a guessing game, a shot in the dark about what was safe and effective.

I had been a registered nurse for only two years when the pandemic hit. I felt woefully unprepared for such a crisis and yet was thrust into a frontline role without preamble, amid concerns for my own safety. I thanked God I had no children in my house and felt for my colleagues who worried about carrying the virus to their children.

The shortage of PPE was alarming and stressful, but by far the worst nursing experience of the pandemic was caring for patients who were suffering and dying alone. With visitor restrictions and bans in effect, hospital staff were instructed to make only strictly necessary entries into each patient room, which resulted in minimal opportunity for conversation or emotional and spiritual support for these patients. We nurses were often their only human contact, and yet, heavily garbed and muffled in our PPE, we were still separated from them by sweaty layers of plastic.

It was probably the saddest and most dehumanizing season of my life. I did everything I could as a nurse for these patients but saw that their deaths were lonely and bereft of peace and dignity. I could not count the number of times I had to turn away visitors at the door or refuse them on the phone as they begged me to let them see their dying loved one. I felt I had failed to provide good care to these patients and families. I would hold back my tears during shifts, then cry on my commute home when tears would not bother anyone or interfere with my work. Once home, I would refuse to touch or hug my husband until I had showered. Then I laundered my scrubs separately from all of our other clothes.

It was hard to summon the courage to reenter the fray each shift. Occasionally I phoned Dad and Grandma. Dad was in the midst of COVID-19 in his own hospital. He was calmer than I was, since he had doctored through H1N1 and other pandemics. Dad also reminded me to think of our forefathers and foremothers in Mennonite medical missions. Despite dangerous circumstances and limited resources, they had ventured into the unknown to deliver healthcare to people who needed it desperately. I understand their stories more keenly now after facing the challenges of being one small team member in a rural ICU without the benefit of proximity or access to the specialized supplies and equipment of my city colleagues.

Doing what was possible in rural areas while constrained by limited resources is precisely what Grandpa and Grandma did for years. I thought about them struggling through the Taiwanese jungle in the medical mobile clinic vans and backpacking their supplies over literal mountains. When I phoned Grandma during the various lockdowns and told her about my work, she never coddled me or felt sorry for me. She did not say, “Oh, I could never do what you do,” which I heard frequently from others. Grandma had a sort of calm acceptance that a hard nursing job to do is still a nursing job to do. Her approach was influenced, I believe, by the backbreaking work she undertook during her years at MCH. Her attitude helped me stiffen my own backbone, re-summon my courage, and keep showing up for shifts and serving however I could.

Pandemic Nurse Art

In the summer of 2020, I started a piece of beadwork art to cope with everything that was happening. The piece is shaped like a circle, outlined by heartbeats. The heartbeats represent both the quotidian heart rhythm strips I analyzed every shift and also the common heartbeat we all share. On the left is a representation of the young jingle dress dancer Skye Yannabah Poola. The jingle dress dance is a healing dance created among North American Indigenous peoples during the 1918 flu pandemic.24 Skye and others like her posted themselves dancing on social media during COVID-19. Alongside the memory of my grandparents’ work, these jingle dancers helped to bolster my courage. On the right of the artwork is an image of myself in some ordinary blue scrubs. On the bottom are incense prayers, and on the top is a stethoscope in a heart shape. The inside of the circle is filled with white. The micro-sized white beads are organized in a variety of orientations and patterns. This represents the ever-shifting nature of the sheer unknown that healthcare workers faced during the pandemic.

I found the art evolving and changing as I worked on it, much like the COVID-19 pandemic itself. I added the white MCC dove into the middle to honor the work of my grandparents in Mennonite medical missions that inspired me to keep going. I also put in a 1-mL Luer-LokTM syringe, the kind of syringe the COVID-19 vaccines are delivered in. For me, the vaccines meant protection from harm and hope for the end of the pandemic one day. When I received my first COVID-19 vaccine, months after I had started pandemic nursing with limited protection from the virus, I almost cried with relief in front of the public health nurse. The vaccine felt like a weight off my shoulders. Ironically, soon after I put that syringe into the beadwork, my workplace was no longer allowed to order them for normal medical purposes; 1-mL Luer-LokTM syringe supplies were, understandably, funneled instead toward the vaccine efforts. For non-COVID injections, we received cheaper “slip-tip” syringes. They did not fit our needles well, but we were expected to make do. It is a tiny detail but one that stays in my memory as an example of things we never anticipated would be pandemic problems.

I also decided to add “star” beads to the outside of the circle to honor the patients I had lost during COVID-19. Each of those stars represents a patient dying alone whose death wrenched at my heart and soul. I did not feel that we honored these patients’ emotional needs or their dignity in their deaths, so I hope to honor them in this work. I like to think of them as looking down on us with love from the spiritual dimension beyond this life.

Finally, I added one special, unique bead to represent Grandpa. I put him close by me looking over my shoulder as I went about my pandemic work. I would think to him, “Grandpa, of all the people who might be able to see me now, you know more than anyone what this journey is like.” I imagined him looking down from heaven, saying, “Yes. I know what this is like. Stay strong. You can do this.”

My Father

Like me, Dad felt his medical practice as a physician hospitalist never measured up to the sheer scope and accomplishment of Grandpa’s work. I believe he has downplayed his impact, however, in his own career. Over the course of more than thirty years of medical practice, Dad has mentored hundreds of residents, training the next generation of doctors. His humble, friendly, and approachable demeanor makes him highly respected and well-liked by doctors, nurses, and patients alike throughout his hospital. It is not uncommon for someone to recognize him somewhere in public, approach him, and thank him for the care they received from him at some time or another. As a child watching these encounters, I had the impression that Dad knew just about everyone in our city.

Continuing the work Grandpa started as a Mennonite doctor, Dad—as the second Dr. Friesen—exemplifies hard work, kindness, and Christ-like love. I believe Grandpa would be very proud of him. In addition, Dad’s calm and reassuring presence through so many healthcare “storms” over the years has been invaluable to young healthcare professionals like me. Although his medical career has not been as outwardly dramatic as Grandpa’s in Taiwan, I firmly believe it has been no less important. Dad does not consider the sheer number of people he has encouraged, uplifted, and cared for—both patients and professionals—throughout decades of quiet service. He should give more credit to his presence and legacy in medicine.

Faith during the Pandemic

Rather than articulating what Christian witness to healthcare systems should look like, I am simply sharing my experience as a Christian who witnessed healthcare systems in the midst of a pandemic. In those terrifying and unforgettable times, I resonated more with God as Sufferer than God as Healer. It did not seem like much physical or spiritual healing was happening, which weighed upon my soul. As I held the hands of the dying in my own gloved hands, I thought that Christ must be present in the horror, because he understands and enters suffering. A person who is “a man of sorrows and acquainted with grief”25 is someone one can cling to during a pandemic, someone who will not run away from the suffering. This thought brought me a kind of grim comfort and helped me to not run away either, to continue despite my grief.

I have heard plenty of sermons about finding joy in hardship. None of them felt meaningful to me during pandemic nursing. Hardship was hardship, and there was no joy in it. What I did find myself receiving instead was grit. When joy was not possible, the Creator gave me grit to keep sticking to the tasks at hand. Some small ember within me never quite died, and I was determined to see the pandemic through, no matter how deep and dark it became. I believe this speaks to grit as a spiritual gift. Though not as beautiful as something like joy, its presence in hard times is an unlikely but welcome spiritual nourishment. I thank God for grit.

The Nature of Mission

Though perhaps not as intrepid and exciting as my grandparents’ Mennonite medical missions, pandemic nursing was the medical mission I landed in. Both required determination, creativity, hard work, physical and spiritual strength, and, above all, Christ-like love. The Mennonite medical missions of my grandparents’ era had an explicit proselytizing purpose. Those mobile clinics brought, in approximately equal measure, the gospel, fortified milk for children, and deworming medications to remote Indigenous villages.26 Chaplains circulated to each patient in MCH to deliver the gospel message and attempt to connect patients with churches after their discharge.27

I do not personally take this approach today. I will not proselytize at the bedside, nor do I feel that to do so is appropriately respectful of patient autonomy. This is likely the influence of my modern values and nursing training. To me, the actions of nursing and medicine are already mission in themselves because they embody the call of Christ to heal the sick, care for the lonely, and, in pursuing health justice, seek freedom for the oppressed. Thus, despite differences of opinion with my forebears in Mennonite medical missions, I still highly respect their hearts, love, and sheer medical excellence. Those doctors and nurses, out of love for Christ, served thousands of people that no one else considered worth the effort. Dickson wrote:

Let me tell you a secret. You have to look at each patient . . . (though their great need of help thunders at one)—as if it were Christ Himself waiting to be ministered to. It makes all of the work a sacrament, holy, happy, exalting.28

May all Christian healthcare providers look at each patient and see Christ himself; may that great need of help still thunder at us. That is our mission, and that is our sacred care. It was an immense sorrow but also an immense honor for me to minister to patients in a pandemic. I could not have done so without the grace and strength of Christ and without the courage my grandparents’ legacy gave me.

I will leave the reader with a poem I wrote during the pandemic, and a final word of encouragement:

pure uncertainty

pure fear

pure confusion

pure determination

pure change

pure adaptability

pure sorrow

pure teamwork

pure tragedy

pure grit

pure grief

pure courage

pure liminality

pure love.

In the words of Grandma’s Indigenous language, saicelen salikaka mapolong (Never give up, keep going, all my relatives).

Monica Friesen is grateful to be hosted in Treaty 7 lands and resides in Mohkinstis (Calgary), Canada. She currently works as a registered nurse in palliative care and Indigenous health research, and is pursuing masters studies in nursing. She is a twin sister, wife, and daughter and is in the early stages of cultivating her auntie energy. She is of Indigenous Austronesian, Mennonite, and Chinese descent.

Footnotes

I will embed a sense of storytelling in the style of this paper because I believe in the power of stories to impact the mind and heart of an engaged listener. For more information about storytelling and the interface of oral traditions in literature, see the discussion of “Indigenous Voice” in chapter 2 of Gregory Younging, Elements of Indigenous Style: A Guide for Writing by and about Indigenous Peoples (Edmonton, Canada: Brush Education, 2018).

Lillian Dickson, These My People: Serving Christ among the Mountain People of Formosa (Toronto, Canada: Evangelical, 1958).

Dickson, 21.

Roland P. Brown, Healing Hands: Four Decades of Medical Relief and Mission in Taiwan (Newton, KS: Mennonite Press, 2017).

Brown, Healing Hands. Dr. Brown’s influence and legacy thread throughout almost every account of Taiwanese Mennonite medical missions.

Mennonite Christian Hospital, “Introduction to MCH: MCH’s Accomplishments & MCH’s Special Accomplishments,” Mch.org, 2010, https://www.mch.org.tw/english/introduction_accomplishments.shtm.

Brown, Healing Hands.

Mennonite Archival Information Database, “Item 2010-14-366,” archives.mhsc.ca, February 23, 2015, https://archives.mhsc.ca/index.php/used-in-cm-7-21-4-information-on-back-of-photo.

Dickson, These My People, 55.

Brown, Healing Hands, 68; Mennonite Christian Hospital, Serving the Lord—The 60th Anniversary, Vol. 2 (Haulien, Taiwan: Mennonite Christian Hospital, 2008).

Roland Brown’s influence and legacy thread throughout almost every account of Taiwanese Mennonite medical missions.

Susan Kehler, Paul Wang, and Peter Huang, “Taiwan Group Celebrates 60 years of Medical Ministry,” Mennonite Mission Network, October 1, 2008, https://www.mennonitemission.net/news/Taiwan%20group%20celebrates%2060%20years%20of%20medical%20ministry. Han Vandenberg’s name lives on today, as many people know my father as “Dr. Han Friesen.”

I have a frail copy of an MCH 1970 calendar depicting the Friesens standing in a mission compound group photo, with their names listed on the back.

MCH, Serving the Lord, 20.

Brown, Healing Hands, 74.

Brown, Healing Hands.

Rosalyn Fei, “Settler Colonialism by Settlers of Color: Understanding Han Taiwanese Settler Colonialism in Taiwan through Japanese American Settler Colonialism in Hawai’i,” Asian American Research Journal 2 (2022), accessed August 16, 2022, https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2mk3z9qk. Fei outlines the experiences of Indigenous peoples of Taiwan enduring several regimes of colonialism, one of which was the Japanese occupation after the Sino-Japanese War. The Japanese forcibly colonized Taiwan from 1895 until their withdrawal in 1948 after WWII. After this, the Chinese Kuomingtang Party enforced a Chinese regime in the country, many vestiges of which remain today. Each colonial regime viewed Indigenous peoples as incapable of being sovereign over our own traditional lands and actively oppressed us and our efforts to resist colonial rule.

Brown, Healing Hands.

MCH, “Special Accomplishments,” https://www.mch.org.tw/english/introduction_accomplishments.shtm.

Fei, Settlers of Color.

Perhaps I should add a caveat that Mennonite medical missions were not immune to the White-centric and male-centric pressures of North American evangelical efforts. One symptom of this was the recognition, at times, of Mennonite staff more than the Indigenous and Chinese-Taiwanese staff, with some notable exceptions. Colonial

legacies in Christian mission are still being untangled today. As a descendant of Mennonite, Indigenous, and Chinese ancestors, I wrestle with these colonial contradictions.

Brown, Healing Hands, 110.

MCH, “Special Accomplishments,” https://www.mch.org.tw/english/introduction_accomplishments.shtm.

Harper Estey, “The History of the Jingle Dress Dance,” Ncai.org, National Congress of American Indians, August 12, 2020, https://www.ncai.org/news/articles/2020/08/12/the-history-of-the-jingle-dress-dance.

Isaiah 53:3 ESV.

Brown, Healing Hands.

Brown, Healing Hands.

Dickson, These My People, 116.