Mennonite World Conference (MWC) in 2022 reported the baptized membership of the Meserete Kristos Church (MKC) in Ethiopia at around 515,000 adult members, making it the largest national body in the global MWC family. Much has been written in other places about the growth of the MKC since its origins through the efforts of local believers and North American Mennonite missionaries in the 1940s, the founding of its first congregation in 1951, the 1959 adoption of its name (Meserete Kristos Church, “Christ is the Foundation Church”), its underground life during the era of Communist rule in the 1980s, and its growth and ministry expansion in the early decades of the twenty-first century.

With its high ecumenical dimension and the significant role hybridity plays in the identity of the MKC, Anabaptist essentials have been tested and reshaped within the Ethiopian context.1 Preparations are already underway in Ethiopia for MKC to host a global Mennonite World Conference Assembly in 2028. From January 11 to 17, 2024, Dr. Henk Stenvers, President of MWC, was in Ethiopia on behalf of Mennonite World Conference, and he joined MKC President Desalegn Abebe Ejo in signing a Memorandum of Understanding.

Meserete Kristos Church President Desalegn Abebe Ejo and Dr. Henk Stenvers, President of Mennonite World Conference, signing a Memorandum of Understanding in January 2024 (in preparation for MKC hosting MWC Assembly 2028 in Ethiopia). Photos by Liesa Unger.

So, there is much to report about MKC and its present activities, but in this issue of Anabaptist Witness, we will focus specifically on the history and current practice of MKC in its mission and peacemaking efforts in the larger Ethiopian national context. Several things struck us as we prepared the collection of twelve essays and three book reviews appearing in this issue.

Christian origins in Ethiopia. First, almost all of the authors writing here have challenged the oft-held assumption that Europeans brought Christianity to Ethiopia. Most of the articles refer to the fact that Mennonite missionaries, arriving in the 1940s, were not the first to introduce Christianity to Ethiopia. Some authors, in fact, attribute the presence of Christianity in the nation to a time predating the gospel’s arrival in northern Europe. This truth might create a “wow” moment for some Anabaptist Witness readers, but for the authors in this volume and in the country of Ethiopia more generally, this is simply a well-established fact that everyone knows and recognizes.

The long relational history between church and state in Ethiopia. Secondly, Anabaptist Witness readers will learn of the centuries-old marriage arrangement between the Ethiopian state and the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church (EOTC). This occurred because Christianity entered Ethiopia in a top-down manner with the conversion to Christianity of fourth-century Emperor Ezana, who, in turn, imposed the religion on the entire Ethiopian population.2 Repeatedly in this issue, reference is made to “the close relationship between the King’s palace ideology and governance and the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church (EOTC) polity and theology” and how this “can be compared to the way that two hands fit perfectly together in gloves.”3 When Socialist ideology (1974–1991), however, began to infiltrate the rich religious and cultural history of Ethiopia, the church and state were, for the first time, divorced officially and the Solomonic Dynasty of Ethiopian Christendom came to an end.

Sources referenced in this volume. In the third place, we were curious to see which sources were referenced by the authors in this collection. To our surprise, we noticed Ethiopian theological materials being used. There is a trend among Ethiopian writers to rely heavily on theological reflections from the West and to integrate these views into the Ethiopian context. The essays found here are not totally free of that influence. But it is encouraging to see writers in this issue reverse the usual impulse by frequently citing the reflections of Ethiopian authors and theologians. Not only are the Ethiopian contributors in this collection engaging in theological reflection in their work, they are doing so by being dependent on other Ethiopian theologians who have articulated theological reflection before them. This is a remarkable and encouraging development and will assist our brothers and sisters in the West to respond to East African professor John S. Mbiti’s concern in his address to Western colleagues and theologians:

We have eaten with you your theology. Are you prepared to eat with us our theology? . . . The question is, do you know us theologically? Would you like to know us theologically? Can you know us theologically? And how can there be true theological reciprocity and mutuality, if only one side knows the other fairly well, while the other side either does not know or does not want to know the first side?4

The rigorous work and theological reflections during the second and third centuries in North Africa by church fathers such as Tertullian, Origen, Clement of Alexandria, Augustine, and others have been accepted by both Western and Eastern Christianity as integral elements of the global Christian heritage. Our prayer and hope are that the articles found here, written by African theologians, can be as important and definitive as ones of the second-century era.

Statistics and ecclesial understandings. The Mennonite World Conference in its 2022 statistics lists MKC membership at around 515,000 members. But some authors here reference as many as 1,000,000 members in the MKC. They include in these numbers children and unbaptized candidates for membership in their statistics. This raises an interesting question about how one understands the extended church family, particularly in light of Anabaptism’s historic emphasis on baptism as central to church membership.

Culturally shaped, contextual terminology. English-language terms hold different meanings in different parts of the world. Readers of this issue of Anabaptist Witness may be surprised by certain terms that they would not use or would use differently in their own cultural setting. Most member churches of Mennonite World Conference, for example, consider themselves to be in the “evangelical” stream of ecclesial bodies—including Ethiopia’s Meserete Kristos Church5—and may even include the term “evangelical” in the title of their denomination. Only a handful of MWC churches are members of the ecumenically minded World Council of Churches (WCC), while many associate with the World Evangelical Alliance (WEA). But readers should not assume that “evangelical” means the same thing everywhere. The Trump era of presidential politics in the United States has heightened the need to be extra sensitive not only to word usage and meaning but also to the fact that the local, contextualized bubble of conversations about and attitudes toward certain terms is not necessarily shared by other members of our global faith family who are living and ministering in very different cultural settings.

A good discipline for readers here might be to make a list of surprising or perceived “problematic” terms or concepts encountered in these articles and then follow up by inquiring of one or another Ethiopian writer or friend what is the use or meaning of that term in their particular sociocultural and historical context.

Western missionary roles and local Ethiopian initiatives. The lives and ministries of Mennonite missionaries are referenced in these articles. Special attention is given to the ways in which they conducted themselves among Ethiopians and the legacy they left behind, impacting many local Meserete Kristos leaders. We are pleased to see this credit given, all the while noting that the most significant church growth occurred when the Ethiopian leadership team took over and the missionaries left the country. In their co-authored reflection, Desalegn Abebe Ejo and Kebede Bekere explain the challenges the church has faced and how the MKC has overcome these obstacles to sustain the growth of the church through “Agenda 28:19”—the current missional initiative among Meserete Kristos churches.6

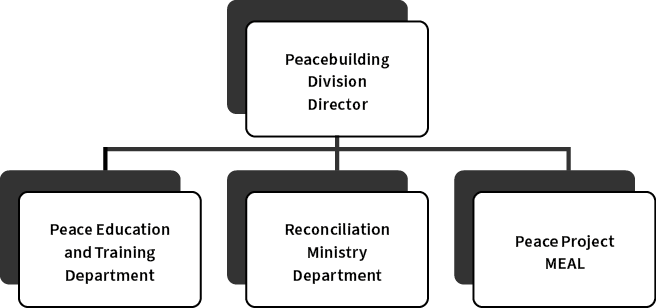

Holding mission and peace together in holistic ways. Several case studies in this collection describe how MKC conducts its various ministries in holistic ways, engaging particular communities in an effort to support impressive peacebuilding and reconciliation initiatives. These are powerful and moving stories, filled with hope in the midst of significant conflict. Meserete Kristos Church is one of only two evangelical church denominations in Ethiopia with a peacebuilding department designed to promote peace, reconciliation, and healing among communities in the country. The MKC Peacebuilding Division has the following organogram:7

Meserete Kristos Church in the broader Ethiopian socioeconomic-political context. We considered including in this editorial more background information about the broader national context in which MKC finds itself. This would be a serious challenge, however, since there is no such thing as neutral history. The existing conflicts on the ground are very complex, culturally shaped, and historically rooted. In the end, each author will provide here the context of their own choosing, setting forth the overall framework of the argument they wish to develop in their article. A few brief words, however, about the Ethiopian context for non-Ethiopian readers, may be helpful for situating the following articles in their demographic, historical, and geographical setting:

1. Population and ethnic identities. The Ethiopian population in 2022 is believed to be more than 120 million, with a majority being youth. The nation is home to various ethnic groups, multiple languages, and hundreds of dialects.

2. Politics. Beginning in 1991, Ethiopia has been using a parliamentary system. Ethiopians do not directly elect their prime minister. Instead, different parties run for election, and Ethiopians elect the party they prefer. Once a party wins the election, that party then chooses the prime minister of Ethiopia. In other words, the party with the greatest representation in the legislative parliament forms the government, and its leader becomes the prime minister. The trend for decades has been that when a party is formed to run for an office of the central government, the members of that party are from one ethnic group, with all of the challenges that this implies. Ethiopia has gone through various styles of leadership, from a feudal theocratic form of governance to socialism (1974–1987) and The Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (1988 to 2019), formed by the Tigrayan people of northern Ethiopia, advocating for “Ethnic Federalism.”

Ethnic federalism is the system of government introduced to Ethiopia in 1991 with the hope of resolving the country’s diverse ethnic realities. This system allows each ethnic group to exercise self-rule in its respective region, to preserve its language and cultural identity, to grant autonomy with authority over constitution and policy-making, and to decide on a working language for their region. Ethnic federalism divided the country into regional states based largely on ethnic and linguistic lines. In reality, however, it has been criticized for politicizing ethnic identity and increasing conflicts between groups.8

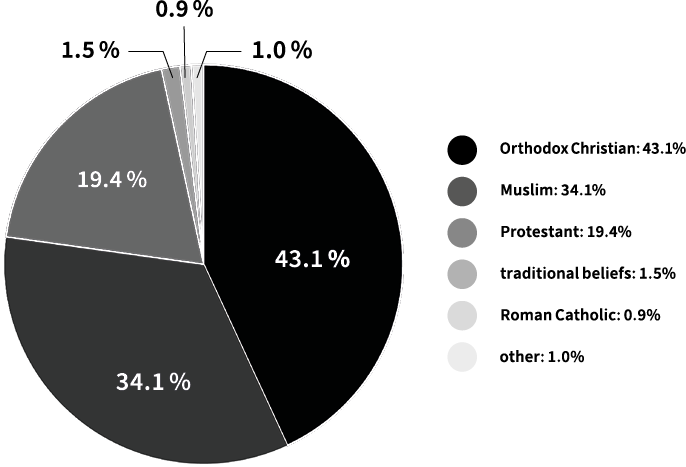

3. Religion. Ethiopia is also home to various religious faiths, predominantly the Ethiopian Orthodox Church—called “Tewahedo” in Ethiopia—which accounts for 43.1 percent of the country’s population, and Islam, which comprises 34.1 percent of the country.9 Almost 20 percent of the Ethiopian population is Protestant, including the Meserete Kristos Church.

Religious Affiliation in Ethiopia (2012): Meserete Kristos Church—the Ethiopian Mennonite church—is considered part of the Protestant tradition. (Reprinted from Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., with permission.)

4. Mennonite arrival and presence in Ethiopia. Mennonite missionaries began arriving in Ethiopia during the reign of the country’s last king—Emperor Haile Selassie I (1930–1974)—in the centuries-long monarchical system. After World War II, Emperor Selassie sought to modernize Ethiopia. It was during this time that Mennonites were granted permission to enter the country and assist the emperor in his efforts to modernize. Being relief workers and trained personnel in different sectors was key to the Mennonites gaining access to the country.10 The imperial government was more accepting of the mission—despite its desires to evangelize—due to the alignment of the Mennonite approach with the development aspect of the imperial agenda.11

5. Relevance to current events in 2024. It is important to note that the matters addressed in this issue of the Anabaptist Witness journal are not simply scholarly or theoretical ones. At the very moment when we were assembling the various articles of this issue on peacemaking initiatives in Ethiopia, an assassination was tragically carried out against a member closely affiliated with the Meserete Kristos Church community. This struck close to home and reminded us of the relevancy of this topic for the biblical grounding of peacemaking, for the recounting of historical precedents in the life of the church, and for contemporary responses to current realities in the Ethiopian context.

Editors’ invitation and request. As we have worked on this issue of Anabaptist Witness, our hope and vision has been that this collection of essays and book reviews would contribute to the sharing of gifts for mutual growth among Anabaptist/Mennonite churches across the globe.12 We would also be very happy to see this as one of the resources to which people turn as global Anabaptist communities prepare to attend the 2028 Mennonite World Conference Assembly in Ethiopia as part of the 500th commemoration of the origins of the Anabaptist movement. The friendly request we have for the English-speaking Anabaptist Witness readers—especially to sisters and brothers in North American and European Mennonite churches—is to set aside some of your English-language expectations for scholarly articles of this nature. Writing scholarly material in English as a second, third, or even fourth language presents challenges for many members of the global Anabaptist family. We have used editorial and peer-review feedback to work with contributors to the journal, but we also intentionally edited the articles with a lighter touch so that readers can be exposed to the writing styles of theologians, teachers, pastors, and academicians in other parts of the world, in this case Ethiopians.

There is so much opportunity for learning and exchange between people, churches, and institutions located in different global contexts if we open up some space to be exposed to and learn what God has been doing beyond our usual relational and conversation circles. In doing so, not only will Anabaptist churches in Ethiopia, Tanzania, Kenya, India, and Indonesia learn what God has been up to far from their home settings, but Mennonite churches in the West will also learn about God’s actions through the church in Ethiopia, India, Indonesia, and beyond. All of us will be strengthened in our faith if we intentionally seek out the voices of sisters and brothers living out their faith in contexts different from our own.

The contributors in this issue have dared to write scholarly articles in English—a language far from the language of their daily use—because they wished to share with Anabaptist Witness readers theological reflections of what God is doing in their own context of life and ministry. We are inviting English-speaking readers of the journal to develop new reading skills in order to “hear what the Spirit is saying to the churches” (Rev 2:7).

The organization of this journal Issue. The articles in this issue are organized in two large sections. The first focuses on mission and peace efforts in the broader context of the Ethiopian nation through a biblical reflection (Yimenu Adimass Belay), an application of the Christus Victor narrative within the Ethiopian setting (Geleta Tesfaye Berisso), and a survey of publications promoting interfaith conversations between Ethiopian Orthodox and Evangelical Christians (Abenezer S. Dejene).

The second section focuses more specifically on Meserete Kristos Church history and perspectives and is subdivided into two parts: (1) The first subsection is entitled “Missionary Influences and Voices,” and is represented by two articles authored respectively by Ruth Haile Gelane and Carl E. Hansen, and an article co-authored by Desalegn Abebe Ejo and Kebede Bekere. (2) The second subsection focuses more specifically on MKC peace and mission efforts in the fields of trauma healing (Kebede Bekere and Mekonnen Gemeda), breaking cycles of “Black Blood” (Amdetsion Sisha), creating safe spaces (Rosemary Shenk), witnessing as a peacemaking “cruciform” community during the revolutionary era (Brent Kipfer), developing a peacemaking culture (Mekonnen Gemeda), and articulating a holistic approach to peacemaking where prayer, evangelism, and justice are intertwined (Henok T. Mekonin).

Three book reviews on various Ethiopian topics round out this issue, featuring a publication on one family’s personal odyssey in Ethiopia—Carl E. Hansen (author), Joel Horst Nofziger (reviewer); a study on interchurch conversations between Ethiopian Orthodox and evangelical churches—Daniel Seblewengel (author), Nebeyou A. Terefe (reviewer); and a volume on the painters, patrons, and purveyors of Ethiopian Church art—Raymond Silverman and Neal Sobania (authors), James R. Krabill (reviewer).

—Henok T. Mekonin (Guest Editor)

—James R. Krabill (Interim Managing Editor)

1 Henok Mekonin, “Anabaptism in Ethiopia: Six Markers of the Meserete Kristos Church,” Vision: A Journal for Church and Theology 25, no. 1 (March 19, 2024): 84–89.

2 Henok T. Mekonin, “A Sense of Pride and Suspicion: Ethiopia’s Habitus and Its Impact on Interactions with Foreigners,” Anabaptist Historians (blog), April 27, 2023, https://anabaptisthistorians.org/2023/04/27/a-sense-of-pride-and-suspicion-ethiopias-habitus-and-its-impact-on-interactions-with-foreigners/.

3 Mekonin, “A Sense of Pride.”

4 John S. Mbiti, African Religions and Philosophy (Garden City, NY : Anchor, 1970), http://archive.org/details/africanreligions00john.

5 Mekonin, “Anabaptism in Ethiopia,” 89.

6 Henok T. Mekonin, “East African Mennonites Hold Summit,” Anabaptist World (blog), April 9, 2024, https://anabaptistworld.org/east-african-mennonites-hold-summit/.

7 “MEAL” in Project MEAL stands for Monitoring, Evaluation, Accountability, and Learning.

8 Namhla Thando Matshanda, “Ethiopian Federalism Has Fuelled Tensions about Clan Histories,” Africa at LSE (blog), June 28, 2023, https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/africaatlse/2023/06/28/ethiopian-federalism-has-fuelled-tensions-about-clan-histories/.

9 Encyclopædia Britannica, “Ethiopia: Ethnic Groups and Languages,” Britannica Academic (blog), accessed April 20, 2024, https://www.britannica.com/place/Ethiopia/Soils.

10 Alemu Checole, “Mennonite Churches in Eastern Africa,” in Anabaptist Songs in African Hearts: A Global Mennonite History, ed. John Lapp (Intercourse, PA: Good Books, 2006), 207.

11 Mekonin, “A Sense of Pride and Suspicion.”

12 Henok T. Mekonin and Rachel Miller Jacobs, “The Postcolonial Mindset and Mutual Gift Sharing: Nurturing Genuine Global Partnerships in the Postcolonial Church,” Anabaptist World (blog), May 17, 2023, https://anabaptistworld.org/the-postcolonial-mindset-and-mutual-gift-sharing-nurturing-genuine-global-partnerships-in-the-postcolonial-church/.