Introduction

This article is a missiological reflection on the conflict between Christians and Muslims in the eastern region of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC).12 The central concern of the paper is the question: how can Christians be witnesses of the Kingdom of God in their relationships to Muslims in that context by embodying the Sermon on the Mount? To set the scene for answering this question, the article starts by surveying the history of the relations between Christians and Muslims in the eastern DRC.

The first Muslims in the area were Arab merchants who came into the country via Tanzania. Over a period of a few decades they introduced a new culture and established a powerful administration in a large part of the east. The arrival of Belgian colonialists in the area during the late nineteenth century destabilized the relatively peaceful relations between Muslims and the rest of the population. Since then this relationship has been characterized by ongoing tension and conflict. In addition to a brief historical description of the foregoing developments, this article explores the key findings from interviews with some Christian and Muslim leaders in the area in an attempt to assess the present relationship between the two religious communities.

After doing context analysis, the article moves to theological reflection, by making a missional reading of some key passages from the Sermon on the Mount (Matt. 5–7).3 This is a contextual reading, which looks for guidance and orientation regarding appropriate ways of doing Christian mission in the eastern DRC. It is a reading that moves from the context to the biblical text, and back to the context. In this process it leads to the proposal for “peacemaking mission” that challenges the existing relations between Christians and Muslims. Finally, some strategies and plans are suggested for this to be a successful peacemaking mission in the DRC.

The theological method used in this study is that of a “praxis cycle,” as proposed by Holland and Henriot4 and later developed by Karecki.5 It constructs a “cycle” of praxis that includes the dimensions of identification, context analysis, theological reflection, strategy and planning, with spirituality at the center. The paper consequently moves from a historical and empirical description of Christian–Muslim tension in the eastern DRC (context analysis), to the development of an irenic approach on the basis of a missional reading of the Sermon on the Mount (theological reflection), and finally to reflection on specific areas of peacemaking mission (strategy and planning). An irenic spirituality and a commitment by the two authors to put these ideas into practice (identification) guide and sustain the whole project.

Brief History of the Muslim–Christian Encounter in the Eastern DRC

Arrival of the Arabs and Islam

For a long time central sub-Saharan Africa remained closed to any contact with the rest of the world.6 The first newcomers were Arab traders who moved south along the eastern coast of Africa and had already established important trading centers along the coast by the eleventh century.7 In the ensuing centuries they moved gradually inland and succeeded in extending their influence into the territory now known as the eastern Congo. By the nineteenth century, this Arab influence had spread into the whole of the east and the north of Congo. After a period of confrontation with the local population, they succeeded in establishing the city of Kasongo, in Maniema province, as the center of their influence, with Kasongo becoming the stronghold of Islam. Unfortunately, Kasongo also became the centre of the Arab slave trade in the region.8

The province of Maniema and the neighbouring provinces of Orientale (in the north), South and North Kivu (in the east), Kasaï (in the west), and Katanga (in the south), were also deeply affected by the Arab slave trade.9 The majority of Muslims in the present-day DRC live in these provinces and they constitute the nucleus of the conflict and tensions that exist between Muslims and Christians to this present day.

An important Muslim trader was Tippu Tip (1840–1905), known in Arabic as Ahmed ibn Muhammad el-Murjebi, who originated from Zanzibar.10 As an ivory merchant who also dealt in slaves, Tippu Tip travelled on several occasions from the coast through central Tanganyika and deep into Congo where his most important business interests were located. He established a powerful empire during the late 1800s. Working between the east coast and Lake Tanganyika, Tippu Tip gradually built up a military force and gained control of the Upper Congo region. When the Belgians made him the governor of the Upper Congo region in 1887, he already had authority over a large territory.11 Tippu Tip appointed his own officials, including many Arab traders, and administered justice. He also negotiated an arrangement between Zanzibar and the Belgians and kept peace among the competing local chiefs. In an effort to expand his business empire, he actually became an influential political leader. Because he was the only person allowed to own firearms in the area for a period, he was able to maintain political domination over a large area. He died in 1891 after returning to Zanzibar and his empire was soon conquered by European forces.

The Belgian colonization and exploitation of the Congo (1877–1960)

When Europeans established their presence in the country, it caused multiple conflicts. One of these was the religious conflict between Christians and Muslims. As pointed out already, by the late nineteenth century Muslims had already established firm control over a large region of the eastern DRC. When Leopold II of Belgium entered the scene to establish his personal kingdom (“The Congo Free State”) in 1885, he wished to demolish that control.12 From 1891 onwards his approach led to open warfare, which gradually also attained the character of a war between Christians and Muslims. This became known in French as the Campagne Arabe (Arab campaign).13 It left a legacy of estrangement among the population, with the tombs of combatants and other memorials at geographical sites serving as reminders of the conflict.14 These sites bring back painful memories until the present time.

The period after this Campagne Arabe was characterized by frequent movements of resistance and open revolt, which continued after the Belgian state took control of the territory from Leopold II in 1908 and it became “The Belgian Congo.”15 The more prominent revolts were those of Batetela in Kasaï (1895), the revolt of the “Arabisés” in Orientale province (1897), the revolt of Shinkakasa (1900), the revolt of rubber collectors in Equateur province (1891–92), and the popular revolt of Bapende in Bandundu province (1931). Sociopolitical movements like Kitawala, which involved the entire Swahili-speaking region, and Mulidi, an Islamic movement, played an important role in the period before independence (1960). The “Muléliste” rebellion lasted the longest and started after independence.16

During the struggle for independence

It is important to note that the resistance movements already mentioned later became associations with a sociopolitical character. Most of these associations became active political parties on the eve of independence.

With the establishment of political parties, Muslims had the opportunity to be heard again. Among the political parties that became influential in Maniema, two were nationalist and radical, namely the Congolese National Movement Lumumbiste (MNCL) and the Centre of African Regrouping (CEREA). Only one was moderate, namely the Popular National Party (PNP). The process of joining these political parties reinforced the confessional split between Muslims and Christians, since the majority of Muslims rallied behind the nationalist and radical political parties (MNCL and CEREA), whereas the Christian leaders joined the moderate party (PNP).17

After the victory of the nationalist parties in the election, Muslim leaders—although less qualified—tried to gain positions of authority in the administrative affairs of the region. This political situation brought back memories of former conflicts. Taking advantage of political identity membership, Muslims seized the opportunity during the Muléliste rebellion to take revenge against the Christians. Christian leaders, who represented a minority in the region, were eliminated.18 As a result, the opposition between the two religious communities became more and more pronounced.

When some order returned at the end of the rebellion, Christians took the opportunity to take revenge against the Muslims, initiating a cycle of violence that persists to the present day.19 It established a climate of hostility that seriously strained the relations between Christians and Muslims, which will not end without a concerted and sustained effort from both sides of the conflict.

During the Mobutu regime

When Mobutu Sese Seko seized power in a bloodless coup in November 1965, the church initially welcomed the new regime and supported the consolidation of its authority. Later, however, Mobutu’s ambitions for state expansion created conflict with organized religion, so that church (both Catholic and Protestant, representing 70 to 76 percent of the population) ironically became the main adversary of his expansionist regime. The role of the church was widespread and its moral authority made it an uncomfortable opponent to the comprehensive political allegiance that Mobutu sought.

The “authenticity campaign” launched by Mobutu’s regime in 1971 was experienced as a direct threat to Christianity. It struck at key symbols of the Christian education system by absorbing both the Lovanium University (Catholic) and the Free University of the Congo (Protestant) into the new National University of Zaire. More problematic to the church was the announcement that branches of the JMPR (the ruling party’s youth wing) had to be set up in all seminaries. The ideological battle centred on Mobutu’s concept of “authenticity,” which the church saw as a direct threat. The regime’s stress on “mental decolonization” and “cultural disalienation” in its authenticity campaign promoted the values of traditional African culture to counteract westernization. When the campaign banned all Christian names, the Zairian bishops briefly resisted, but then backed down. In 1972, the regime banned all religious publications and dissolved church-sponsored youth movements, insisting that the indoctrination of Zairian youth was the prerogative of the Party. This campaign reached its climax at the end of 1974 when the regime nationalized all religious schools, banned the public celebration of Christmas, and restricted the display of religious symbols to church buildings.20

In 1974, some measures were taken for the freedom of religion, which established a kind of religious equality in the Congo.21 In this process, the church lost its favored position and advantages it had enjoyed under Belgian colonialism, and Islam emerged as the third most important religious confession in the country.22 Since then, the conflict has moved into its current phase.

Manifestation of Tension between Christians and Muslims

Sadly, the legacy of violence in the eastern DRC continues. It has become a zone of military operations, an area of rebellion that provides shelter to both refugees and armed militia. It remains a terrain of tension and ongoing conflict. The present situation of Christian–Muslim relations in that context was investigated by means of interviews in 2006 and 2007.23

Two main trends emerged from these interviews, carried out with representatives of the two religious communities in the eastern Congo: a more positive and a more negative approach.24 In the following we give examples of these contrasting attitudes that were encountered in the two religious communities.

Illustrating Negative Attitudes

Muslim opinion

Referring to the memories of the war, an informant from the LMM group said: “The war took place in the past. The Muslims were put in chains and maltreated. There was a fight against Islam expansion in Maniema: the Muslims were pursued and relegated. Mutinies were livid…. Nowadays, we experience provocations from the newest churches. Among the leaders of Revival Churches we mention Kutino in Kinshasa and here in Kindu, we have Pastor Kosaamani Macaba who defamed the Quran…they describe the Muslims as lazy and will then cause these conflicts between the Muslims and the Christians.”25

Moreover, speaking about marriage between members of the two communities, one group of Muslims said: “If you could marry our daughters, we would separate from both of you. If you take her away against our will, we will get rid of the girl and exclude both of you from our community; she will not be part of us anymore. Moreover, we will curse her forever and chase her away.”

Conversion to any other religion is regarded as apostasy, which must be punished with death. A group of Muslims said it clearly: “According to Islamic law, apostasy is a crime which is punished with the death sentence.”

Christian opinion

Speaking about the social impact of Muslims, a PLEP/K group argued that: “Islam brought along atrocities to Congo; it should be compared to an open ulcer, a wound which cannot be healed.” Some others supported that by saying: “In our opinion, a Muslim is a pagan.” They went on to reaffirm that: “Islam is actually a consequence of a lack of true faith in God…people collected some segments of the Bible which were badly transmitted and interpreted, which consequently became the Qur’an.” The same negative attitude was found on the side of Muslims against the Bible. This is the way Christians and Muslims judge each other.

Illustrating Positive Attitudes

Muslim opinion

According to the LMK, a sense of common identity and unity among Congolese Muslims and Christians could contribute to the achievement of peace. Other groups of Muslims claimed a common spiritual heritage with Christians: “Abraham was a monotheist believer and he bequeathed this heritage to his two sons, Ishmael and Isaac. However Ishmael incarnates the Muslims today and Isaac incarnates Christians as well as the Jews.” Such a sense of family belonging could contribute to peacemaking.

Christian opinion

The PLEP/K also emphasized the common Abrahamic heritage as a potential unifying factor: “Both Christians and Muslims are the wire [sic] of Abraham. Abraham as the common ancestor becomes a focus of attention for Christianity, Islam, and Judaism. If they start from Ibrahim or Abraham as the father of the faith, there will never be friction. Abraham, the common ancestor, as well as Isa the prophet are an undeniable historical reality.” They further stated that: “We are serving the Prince of peace. For this reason, we should carry that image in us to build peace within society.”

Controversial Issues

In spite of these positive trends, there are some controversial issues that keep on creating tension.

Interfaith marriage

Muslims expressed a strong opinion against marriage between a Muslim woman and a non-Muslim man.26 It is prohibited in terms of Islamic law: “Basically, Islam does not allow a believing woman to get married to a non-Muslim; it is idolatry. Such prohibition is to preserve the faith and good behaviour. Islam recommends submission to Allah, the unique God” (CEU informant). If a Muslim woman does not submit herself to this rule, she is disowned and even cursed by her family.

Conversion

Conversion is also an emotive issue, with both religious communities expressing firm rejection. From the Muslim side, a CEU informant, quoting Surah 109, said, “It is a loss of faith in Allah, the unique God.” A LMM informant added, “When somebody adheres to Christianity, it brings radical change. Spiritually he is no longer a human being, he becomes like a magician. He is blinded by the belief of a certain Jesus, God. For us Muslims, such a person becomes profane. He is like somebody who has his eyes bandaged and closed to accept profane beliefs.”

On the other hand, a Roman Catholic leader said: “If somebody says to you that he is a follower of Islam that means that he is still a pagan and must be converted. In fact, someone can call Islam a religion, but for us, it is closer to paganism since they do not meet the requirements to be Christian.”

The use of money

The PLEP/K group expressed fear that financial assistance given to poor Christians by Muslims could lead to conversion: “It becomes very dangerous, because for the sake of faith, one can consent to offer himself even by dying.” AMC argued strongly that: “Christian believers must abstain from any Islamic assistance. Anyone has to banish material and financial interests so that he can stand firm in his faith. Denying Jesus because of money is to compromise one’s beliefs in a dangerous way.” PLEP/K added, “If you abdicate your faith, you must be excommunicated from the community of believers.”

Resources for Peacemaking

A number of people interviewed pointed out that peace would be possible if all available resources were mobilized for that purpose. Some Christians emphasized that “it is a loss on the part of Christians if they don’t act peacefully among Muslims. The concept of shalom covers all the good aspects that are integral to a healthy society” (AMC informant). As “children of Abraham,” both Christians and Muslims have much in common. On the basis of a common Abrahamic faith, Christians and Muslims should mobilize their shared ubuntu traditions for the sake of peace.27 These are crucial factors in building a common home, which could be called the “house of shalom.”

Another positive factor is the unifying identity of African religion. African people remain attached to the ethos (or mentality) of their culture, religion, and morality. Resistance to change is a significant motivation in the religious behaviour of many African people, in view of their cultural and political circumstances. African people converting to a new religion (like Christianity or Islam) publicly practice the rituals of their newfound faith to show that they have become believers, but often those Christian and Muslim religious practices unconsciously have a different significance due to the deep-seated motivations and thought patterns of African religion that persist in their lives.28 In this unobtrusive way, African religion still plays a fundamental role in shaping the lives of African Muslims and Christians alike. Consequently, the believers belonging to different “new” religions have a common history in their culture, morality, and religion. Instead of developing hostility to each other or to African religion, African believers who become Christian or Muslim can make use of the values of African religion to enrich their faith in God the Creator. This opens a way to building peace within society.

Finally, there is also the positive factor of Scripture. Starting with the Bible, Christians can become advocates of peacebuilding by learning how to embody the message of shalom, which is so clearly expressed in the Sermon on the Mount.

The Outline of an Irenic Approach

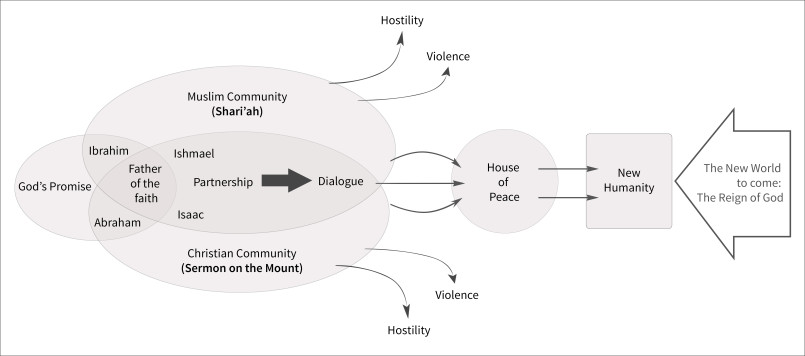

Figure 1 suggests how the different peacebuilding resources mentioned above could be mobilized in a situation where there are significant numbers of Christians and Muslims in a community. It outlines the “space” that neeeds to be created to build convergence between the positive peacebuilding strengths present in both religious communities. It requires engagement in a path of dialogue for peacebuilding—in the eastern DRC and elsewhere. The starting point is the figure of Abraham, as role model of how God’s hand operates in history to initiate a project of gathering new humanity within a house of shalom. The dynamic of this initiative is based on the promise of faith and the obedience of Abraham. Abraham is the father of numerous people, through whom all the families of the earth will be blessed (Gen. 12:3). Through Abraham all the families of the earth, which constitute humanity, should find “well-being,” “integral peace,” and “the plenitude of the salvation in God.”29 In this perspective God becomes the architect and author of an inclusive and embracing house of shalom.

Placing the Muslim community at the top of Figure 1 does not suggest a position of superiority. Figure 1 should rather be seen as viewing the two communities “from above,” as they strive together to create a new future for society. It is intended to portray them as working side by side, “shoulder to shoulder,” as they move ahead towards the coming reign of God.30

Figure 1 presents the two religious communities as striving to counter the divergent forces that constantly threaten to polarize them into opposing “camps,” which would increase the risk of exclusion and violence.31 The more entrenched and ideological they allow their differences to become, the greater the likelihood of ongoing confrontation, leading to an escalating spiral of violence.32 This often happens when the religious symbols and practices of the two communities are used to rationalize and legitimize economic and/or political interests and power struggles in a society. When that happens, the future of the house of shalom is threatened by deepening polarization and antagonism.

Figure 1 presents the possibility of creating a space of convergence through mobilizing resources from both religious communities on a path of dialogue and collaboration for peacebuilding. There is a need to establish sufficient common ground between the two religious groups to build a solid foundation for lasting peace. With respect to the eastern DRC, one could suggest the following aspects:

Affirmation of a common spiritual legacy in Abraham, the father of believers;

Attachment to principles of ubuntu, which recognizes the dignity of each human being and respect for African cultural values;

Recognition of a common national identity;

Recognition of and total respect for the current constitution and its structures, while waiting to eventually negotiate a new constitution;

Commitment to participate actively in the construction of the house of shalom.

If these resources (and others flowing from them) are mobilized effectively, it is possible that common ground could emerge for a deepening dialogue and collaboration between the two groups. Doing so is an attempt to make the two religious confessions aware of their interdependence within a community of human beings created in God’s image.33 It is necessary for Muslims and Christians to collaborate across religious barriers and collectively focus on addressing the urgent common problems of starvation and poverty that the DRC is facing. They can do this on the basis of God’s promise to Abraham, in expectation of the coming of the Lord’s Day, and by erecting signs of the coming reign of God through shared action for peace in the world.

The escalation of violence should be avoided at all costs in the eastern DRC—and everywhere else. It is the role of religious communities, and particularly of religious leaders, to make civil society and government aware that every person who practices violence sets in motion (or perpetuates) a process of the ongoing renewal of violence. Violence imprisons those who practice it in a “vicious” circle that is very difficult to break, once it has gone beyond a certain “tipping point” of mutual exclusion and hatred. This is what Ellul calls “the law of violence.”34 It is the calling of Christians and Muslims, as descendants of Abraham, to work side by side against this destructive “reproduction” of violence.

A Missional Reading of the Sermon on the Mount

As alluded to earlier, the Sermon on the Mount (Matt. 5–7) is one of the key resources that Christian leaders and theologians could use to mobilize Christian communities for peacebuilding action in society. What is needed is a contextual and missional reading of the sermon that interprets the passage as a call to Christians to build an irenic partnership with Muslims in the eastern DRC. The sermon is about the “good news of the kingdom of heaven,” which is the “gospel of peace” that Jesus Christ was charged to proclaim. This proclamation was the aim and focal point of his mission. From this “gospel of peace,” Jesus affirmed through his teaching and deeds how the reign of God was already present among people.35 The missional reading of the sermon in this article concentrates on three passages: Matthew 5:9–12; 5:43–48; and 5:11–12 (in this order).

A Peacemaking Identity (Matthew 5:9–12)

The analysis of the interviews above has revealed a distinct level of hostility between Christians and Muslims in the eastern DRC. The question is: what direction or guidance can one find in a passage like this to address such challenges? Matthew 5:9 reveals the basic orientation of a life of discipleship in and towards the reign of God. The two important Greek expressions in the verse are eirenopoioi and klethesontai huioi theou. Most English Bibles translate eirenopoioi as “peacemakers” (NIV), similar to the Vulgate, which rendered it as pacifici, from “pax and facere”: peacemakers.36 The focus is on “doers of peace” or, as the New Living Translation (NLT) puts it, “those who work for peace.” This, in our view, captures the meaning of the verse quite well. It suggests an active participation by the disciples of Jesus in creating peace wherever there is hostility. That was the project of Jesus, who called his disciples to be “activists for peace” or “peace workers.”37 This reveals their identity as God’s children who imitate their “heavenly Father” by becoming “creators of shalom”: “those whom Israel’s god will vindicate as his sons will be those who copy their father; and that means peacemakers.”38

The second expression, klethesontai huioi theou, is translated as “they will be called sons of God” (NIV) or “God’s children” (NLT), where the term “sons” includes both male and female disciples. The verse reinforces the bond between God’s active children on earth and their “heavenly Father.” It marks a new identity for those working actively for the establishment of the reign of peace. This verse contains more than a promise of future blessing; to create peace in a violent world is to experience the presence and joy of the coming reign of God here and now. Eirenopoioi are the activists who find their identity in working for the manifestation of peace, justice, and salvation, which represent the arrival of the messianic reign.39 Shalom becomes a reality when people experience integral peace—salvation in all its dimensions—according to God’s original covenant plan. In addition to this qualitative aspect, God’s promise to Abraham also has a quantitative dimension: through Abraham God blesses the whole of humanity. This gives meaning to the change of Abraham’s name from Abram, “father is exalted,” to Abraham, “father of a multitude (of nations)” in Genesis 17:5.40 Social injustice, sufferings, and hostility should be considered as a lack of shalom and a threat to the divine plan of peace,41 but the absence of armed conflict does not necessarily mean the presence of shalom. It is fully present where people live in harmony with themselves and with God and where the structures of society embody this.42

Since the attempt to establish such comprehensive shalom represents a threat to some vested interests and power relations in society, peacemakers often encounter resistance and their work therefore requires sacrifice. That is why Matthew 5:10, “blessed are those who are persecuted for righteousness’ sake,” follows directly on verse 9. A key distinguishing mark of these peacemakers is that they are not motivated by the desire for power or revenge, so that they do not retaliate when opposed. The house of shalom that they are building has its foundation in an inclusive love that extends even to their enemies.

Love of enemies (Matthew 5:43–44)

Love for one’s enemies opens the prospects of a house of hope and shalom that all Abraham’s descendants can build and inhabit together. Such an approach is what the Sermon on the Mount projects as the vision of the messianic community.43 On this basis Christians cannot consider Muslims (or anyone else) as enemies to be conquered at all costs. Since Muslims are fellow human beings bearing the image of their heavenly Father, and are joint heirs of God’s promises to Abraham, Christians should regard them as brothers and sisters within the family of Abraham. If Christians could show love to Muslims consistently, their testimony for peace would become powerful. However, to release the transformative dynamics required to make such a relationship possible, a close reading and faithful embodiment of the Sermon on the Mount is essential.

In Matthew 5:43–44, Jesus shows a way to transform broken human relationships, bringing an innovation in the understanding of neighborly love.44 The Torah instructed believers to show love to all the members of the covenant community, particularly to relatives and kinsfolk (e.g., Exod. 20:16–17; Lev. 19:1–18). That love included aliens and foreigners (e.g., Lev. 19:34; Deut. 10:18–19), but not the enemies of Israel. There is no command to Israel in the Old Testament to hate their enemies (as implied in Matt. 5:43), but some psalms (e.g. 83, 94, 109, 137, 139) show that the sentiment of hating one’s enemies was not completely absent. It was a “popular maxim” among Jews at the time of Jesus,45 which was particularly evident at Qumran, where the War Scroll (I QS, 9–10) contained a command “to love all the sons of light…and hate all the sons of darkness.” It is possible that Matthew 5:43–44 was responding directly to this attitude prevalent in the Qumran community.46

Jesus calls his disciples to be consistent peacemakers by loving even their enemies (5:44). By doing so they build an inclusive and nondiscriminatory identity that links them with their “heavenly Father” (5:48) who shows his goodness to good and bad alike. The disciples are called to a way of life that aims at transforming their environment into a house of shalom. Due to the resistance and rejection that peacemakers often encounter, however, it is important for them to develop a resilient spirituality that can sustain this countercultural lifestyle. The spirituality encouraged by the Sermon on the Mount is based on the reign of God as a gift, pronounced over the “poor in spirit” and over those who hunger and thirst for righteousness. It is a spirituality of receiving the promises (indicatives) of Matthew 5:13–14 (“You are the salt of the earth”; “you are the light of the world”) and of embodying them in daily practice. It is also a spirituality of imitating the divine example of inclusive agape by becoming “perfect” in loving both the just and the unjust (Matt. 5:45). It is a spirituality that Jesus not only preached but also practiced on his way to the cross. He endured the suffering of the cross due to his sacrificial love for his enemies.47

Peacemaking and suffering (Matthew 5:11–12; Isaiah 53:1–7)

As stated already, peacemakers often experience hostility and rejection. These two passages express the notion of the “suffering servant(s)” of the Lord and of the redemptive potential of their suffering. For the disciples on their healing and peacemaking mission, suffering is neither a new nor a surprising experience. Matthew 5:12 makes the remarkable claim that the faithful disciples of Jesus who suffer ostracism and humiliation on his account stand in the tradition of Elijah, Amos, Isaiah, and Jeremiah (and other prophets) who endured persecution for speaking God’s word fearlessly to Israel and Judah.

Matthew 5:12 also highlights an additional dimension of the spirituality of peacemaking mission: rejoicing in persecution as a mark of authentication for prophetic witness. It seems that the “school of suffering” is an integral part of the training of peacemakers working for the coming of God’s reign. The way of peacemaking presented by the Sermon on the Mount is not that of an intervention by a powerful outsider who “rushes in to solve the problem.” It is rather the way of identification and accompaniment, characterized by the willingness to bear the pain of estrangement and to love the “unlovable” parties in the conflict. It is also the way of rejoicing at a “reward in heaven” since a life spent sacrificially in peacemaking mission has eternal significance.

Only those who are prepared to be “suffering servants” are suitably qualified to generate peace in a violent world.48 This gives new relevance to the notion of the “wounded healer” developed by Henri Nouwen, who “must look after his own wounds but at the same time be prepared to heal the wounds of others.”49 Peacemaking mission in deeply divided societies like the eastern DRC requires the admission that one is involved in the “problem” and not a neutral observer. Kahane gives a helpful description of the “reflectiveness” required for peacemaking in situations of entrenched conflict:

To create new realities, we have to listen reflectively. It is not enough to be able to hear clearly the chorus of other voices; we must also hear the contribution of our own voice…. It is not enough to be observers of the problem situation; we must also recognize ourselves as actors who influence the outcome. Bill Tolbert of Boston College once said to me that the 1960s slogan “If you’re not part of the solution, you’re part of the problem” actually misses the most important point about effecting change. The slogan should be, he said, “If you’re not part of the problem, you can’t be part of the solution.”50

A Christian community that embodies the Sermon on the Mount will admit its complicity in a conflict situation and be willing to commit itself to peacemaking mission, even if that requires suffering. In the words of Kenneth Cragg, veteran interpreter of Christian–Muslim relations, “In our time we may be unable to see the way out of the human problems of the world. But the way in is clearly evident. It is to invest our lives in the service of those problems as they bear upon people.”51

Abraham as father figure

It is highly significant that Matthew began his Gospel with the words: “An account of the genealogy of Jesus the Messiah, the son of David, the son of Abraham” (1:1). As a “Jewish” Gospel written for a community of Jewish Christians, probably in Syria, before the “final and absolute break with the synagogue had arrived,”52 Matthew highlights the continuity between the message of Jesus and the Hebrew Bible by presenting Jesus the Messiah Christ as the descendant of Abraham and David. The continuity of the power of the kingdom of David opens the channel that ensures the effectiveness of the promise made to Abraham for all the nations. Abraham is the key figure ensuring his role as the witness and guarantor of the promises that bound God to Israel, God’s covenant people. Abraham is also the vital agent who ensured the transmission of spiritual virtues to his children and future generations. This is the reason why Abraham could not remain a mediator of salvation exclusively for Israel; he is, rather, the new beginning of a history of blessing, made possible by God, for the renewal of humanity. Abraham’s faith history served as anticipation of the message of salvation for the nations.53 Abraham became the ancestor of Israel and of the multitude of people to whom God would grant his blessing. It is in all other families on earth that the purpose of God’s promise to Abraham will be fulfilled.54

Ishmael, through whom Muslims trace their spiritual ancestry to Abraham, is not identified as the “son of the promise” in the Hebrew Bible; but he was circumcised and as such carried the sign of God’s covenant. Even when he had been sent away, he still remained under the special protection and blessing of God. The bond of affinity between Isaac and Ishmael, as Abraham’s two sons, was so strong that it was not destroyed by the hostility surrounding the sending away of Hagar and Ishmael from Abraham’s household. Significantly, Genesis 25:9 says: “His sons Isaac and Ishmael buried him in the cave of Machpelah.” The two brothers buried their father together, united in their grief and remembrance of him. As a result, Abraham will always be regarded as the spiritual father of Jews, Christians, and Muslims. He can possibly serve as a unifying figure to bring Christians and Muslims closer together in the eastern DRC. Around the towering figure of Abraham, as “father of all believers,” it may be possible to strengthen the fragile process of reconciliation between these two religious communities in the eastern DRC.

The story of Abraham is the powerful testimony of a man who had a personal experience of journeying with the living God. The Hebrew Bible does not offer a theological discourse to the world, but Christians and Muslims have argued endlessly over him.55 However, the way of “exceeding righteousness” in the Sermon on the Mount (Matt. 5:20) and the “more excellent way” of 1 Corinthians 13 point us in a different direction altogether: This way of peacemaking mission calls us to stop seeing each other as infidels or apostates. Christians and Muslims should begin to accept one another as brothers and sisters in the family of the God of Abraham, and embark on a shared pilgrimage of interreligious dialogue. Instead of only having a face-to-face relationship (often characterized by confrontation and mutual accusation), Christians and Muslims as descendants of Abraham are summoned to adopt a basically shoulder-to-shoulder position to each other, committing themselves to the way of love.56

Strategies for Peacemaking Mission

Since peacemaking mission requires deeds rather than mere words, practical projects are needed to promote peace in communities. We suggest three areas in which peacemaking projects could be developed, with specific reference to the DRC.

Bread for Peace (Pain pour Paix)

In the social field, the “Bread for Peace” initiative (Pain pour Paix, abbreviated to PP in French) was established in Lubumbashi, Katanga, the southeastern province of the DRC. In order to concretize the peacemaking vision of the Sermon on the Mount in the DRC, one cannot limit oneself to spiritual reconciliation. The peace that Jesus, the bread of life, brings to society includes a material peace which has to do with the sharing of bread. Sharing one’s food is a vital dimension of peacemaking, since the modernist separation between spiritual and material makes no sense in Africa and cannot be justified from Scripture. Emmanuel Katongole comments as follows on the words of Jesus to his disciples, “You give them something to eat” (Matt. 14:16):

Through his response, Jesus resists the spiritualization of his ministry. His ministry is not simply about a spiritual message to be listened to and later applied. The Good News that Jesus proclaims is a material vision, which involves the reordering of such material realities as geography, time, food, bodies, and communities.… Jesus’ response is a full-fledged social vision—a social vision that is radically different from the one assumed by the realism of the disciples’ suggestion to send the people away to the villages to buy food for themselves.57

It is not meaningful to engage in abstract dialogue with someone who is starving. In peacemaking mission, Christians are summoned to embody the social vision of Jesus by affirming human solidarity with those who suffer and by sharing what they have. This is at the heart of the prophetic Judeo-Christian-Islamic tradition, namely that worship and peace-with-justice may never be separated. A passage from the Hebrew Bible puts this very clearly: “Is not this the fast that I choose: to loose the bonds of injustice, to undo the thongs of the yoke, to let the oppressed go free, and to break every yoke? Is it not to share your bread with the hungry, and bring the homeless poor into your house; when you see the naked, to cover them, and not to hide yourself from your own kin?” (Isaiah 58:6–7). Such an approach does not merely create a conducive environment for dialogue and peace; it is dialogue-for-peace.

A great deal of crime and violence perpetrated among the religious groups in the DRC and elsewhere originates in communities where poverty, unemployment, and hunger have become endemic. Peacemaking mission cannot adopt an individualistic approach; it seeks to address personal needs but also structural and power issues that affect the lives of whole communities. Even people who appear well-to-do are often famished, languishing in misery, unable to pay their debts, unemployed and resentful. Often people in such positions get drawn into crime syndicates or mob violence. In such contexts, organizations like PP can create the space for new processes of affirmation and solidarity to become a reality.

This can help initiate social dialogue and provide food and other material resources to needy communities, without consideration of their ethnic identity or religious belief. It can also foster discussion between Muslims and Christians of their common interests in social and economic development. Organizations like Bread for Peace, and equivalent movements in the Muslim fold, can contribute substantially to building the house of shalom in broken and suffering communities across the world.

The establishment of consciously interfaith relief organizations could also help to make it clear that the aid is not intended to “score points” for, or attract converts to, a particular religious community. An example of this is Gift of the Givers, a South African nonprofit organization that provides relief and support to communities in crisis. It was initiated by a Muslim medical doctor, Dr Imtiaz Sooliman, and has succeeded in drawing widespread support from Muslims, Christians, and people from other religious communities in the service of suffering humanity.58

Educating for peace

As intimated above, one should not think idealistically about Christian–Muslim collaboration, since power issues often intrude. It is necessary to address the persistent temptation for religious communities to use aid to poor communities as inducement to conversion. Both Christian and Muslim communities need to be educated to renounce this temptation in the spirit of their ancestor Abraham, who delighted in practicing hospitality for its own sake, in order to be a caring neighbor.

The shared journey of faith suggested above also requires breaking down the caricatures of one another that have been developed by both groups over the centuries. Miroslav Volf has pointed out that the way of exclusion (and eventually violence) begins with language, with the words we use to designate or address each other.59 This journey of faith therefore requires dealing with the widespread ignorance and misinformation about the beliefs and values held by other religious traditions: “Symbolic exclusion is often a distortion of the other, not simply ignorance about the other; it is a wilful misconstruction, not mere failure of knowledge.”60

Overcoming this way of exclusion means to begin speaking honestly about people of other religions, their beliefs, and practices, particularly when they are not present to explain or defend themselves. This is the “back-to-back” posture of love as “truthfulness” to which we referred above.61 This implies, among many other things, a thorough revision of all the instructional material used in nurturing Christian and Muslim believers in their respective faith traditions. Peacemaking mission involves a “politics of recognition”62 and an affirmation of “the dignity of difference,”63 so that it becomes possible to build a home of peace together.64

It is also important to take note of various initiatives to draw up a “missionary code of conduct” to regulate or discipline the “evangelizing” activities of religious communities.65 Declarations are not enough, however. The reception of such statements needs to be facilitated and fostered in religious communities, particularly through education. New Christian and Muslim leaders need to be nurtured to influence their religious communities at large towards a peacemaking ethos. One concrete example is the University Peace Centre (Centre Universitaire de Paix, abbreviated to CUP in French) in Bukavu in the eastern DRC.66 As its name indicates, the CUP is a platform for peace education. It educates Christian missionary candidates and other professionals as peacemaking agents, and could become a prototype for other educational institutions in the DRC. Higher education institutions have the responsibility to nurture peacemaking activists for every sector of public life in order to stop the cycle of violence which has become rampant in eastern DRC.

Justice and peace: implementing shari’ah?

The final dimension of peacemaking mission that we address may prove to be the most fundamental to Christian–Muslim relations in the medium and long term. Most Christians are ignorant of the Islamic understanding of shari’ah, partly due to sensational images of severed hands in the popular media and partly due to the widespread modernist assumption among Christians, particularly in the global north, that religion is a private matter with nothing to say for public life. In countries where Christians share life with a significant percentage of Muslims, they face the challenge of the Islamic vision of a theocratic state embodied in shari’ah. On the one hand Christians, particularly Calvinists, are attracted to the Islamic vision of the lordship of God over every domain of life, but on the other hand they are suspicious and fearful of the “second-class” status to which Christians and other religious communities are often relegated when shari’ah is implemented in an Islamic state. They are also painfully aware of the harm and violence that was done in the past by political systems based on theocratic Christian visions, and are understandably careful not to repeat those mistakes.

It is our conviction that there is a way between these one-sided and polarizing alternatives. It is a way in which Christians and Muslims jointly strive to give public, legal shape to the vision of peacemaking mission developed in this article. This will mean mobilizing the public justice resources of their respective faith traditions for the common good, by trying to find a viable political consensus on shared public values, structures, and processes that could embody the key principles of shari’ah as well as the holistic kingdom vision of the Christian tradition. In addition to honest interfaith dialogue, this will also require serious interdisciplinary reflection among theologians, legal scholars, economists, political scientists, sociologists, and other interested parties, since the aim will be to design a “hybrid” democratic state that moves beyond oversimplifications like “secular” and “theocratic.”67 Contributions from the Jewish strand of the Abrahamic tradition will also be vital in this debate, especially the covenantal emphasis of someone like Sacks.68

Christian theologians concerned with “public theology” have started taking this interfaith dimension seriously, emphasizing the importance of living with pluralism and working for a “communicative”—rather than an “agonistic” or a “liberal”—civil society.69 Storrar goes further to suggest that the three “publics” of theology identified by David Tracy (church, academy, and society) should be supplemented with a fourth in the pluralist global era of the twenty-first century: “that of the world religions and inter-faith relations.”70 According to him, this kind of public theologizing requires new resources and skills: “They are the theological resources that can affirm common ground through dialogue and diverse commitments with civility. They are the skills of cross-cultural communication and contextual understanding. As Bosch shows, they are the skills of true evangelism and interfaith dialogue.”71

The surprising thing is that Storrar, in two seminal articles on public theology, while emphasizing the crucial importance of interfaith dialogue, does not quote a single author from another faith tradition!72 The time for such “talks about talks” is clearly over. In the African context, as everywhere else in the world, Christian and Muslim leaders and scholars need to start in-depth dialogues on how God’s will for public life—as they variously understand it—could be embodied in shared societal values, structures, and processes. When the debates among Muslim scholars on democracy and shari’ah,73 and the debates among Christian scholars on the reign of God, law, and democracy are brought together, something significant could emerge for the good of African societies.

Conclusion

This study has highlighted the legacy of Christian–Muslim tension in the DRC and the spiritual resources for peacemaking mission that are available to Christians in an Abrahamic reading of the Sermon on the Mount. It has also identified three broad areas of action (relief, education, justice) in which Christians and Muslims could collaborate to build the house of shalom together, especially in conflict-ridden African societies. The responsibility to pursue this joint peacemaking mission is more urgent now than ever.

Footnotes

Dr. Philemon Gibungula Beghela is a Mennonite from the Democratic Republic of Congo who currently researches mission studies in Winnipeg, Manitoba. Professor J.N.J. Kritzinger teaches missiology at the University of South Africa, in Pretoria. Dr. Gibungula Beghela and his family were the first missionaries sent after the 1997 genocide to plant Anabaptist churches in the Great Lakes region of the DRC. In 1999, they founded a higher education institution for mission and peace studies in Bukavu, in eastern DRC. This institution, the Centre Universitaire de Paix, continues to make significant contributions by bringing Anabaptist mission theology to bear on conflicts such as those examined here involving Christians and Muslims.

This article is based on Dr. Gibungula Beghela’s DTh thesis in missiology, which was supervised by Professor Kritzinger. The thesis is entitled “Vivre l’évangile de paix parmi les Musulmans à l’Est de la Republique Democratique du Congo: Une lecture missionale du Sermon sur la Montagne” (doctoral thesis, University of South Africa, Pretoria, 2010).

The term is used in so many different ways that I should specify how I am using it. In this paper the term “missional” is not used in the technical sense of the Gospel and Our Culture Network in the UK and USA as part of the “missional church” movement, but as an inclusive term to encompass both “mission” and “missiology.” For us a “missional” reading of a Bible passage is neither a narrowly missionary nor a narrowly missiological reading, but an attempt to integrate both these perspectives.

Joe Holland and Peter Henriot, Social Analysis: Linking Faith and Justice (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis, 1983).

Madge Karecki, ed., The Making of an African Person: Essays in Honour of Willem A. Saayman (Pretoria: Southern African Missiological Society, 2002).

Verney Lovett Cameron, A Travers l’Afrique: Voyage de Zanzibar à Benguela (Paris: Harmatan, 1977), 75.

Cameron, A Travers l’Afrique; cf. Georges Hardy, Vue Générale de l’histoire de l’Afrique (Paris: Librairie Armand Colin, 1948).

Isidore Ndaywei e Nziem, Histoire générale du Congo: De l’héritage ancien à l’âge contemporain (Bruxelles: Ducolot, 1997), 235–36; Robert Cornevin, Histoire du Congo-Léo (Paris: Editions Berger-Levrault, 1963), 75; Cameron, A Travers l’Afrique, 75–76.

Cf. René Jules Cornet, Les Phares verts (Bruxelles: Editions L. Cuypers, 1965).

Ndaywei e Nziem, Histoire générale du Congo, 237.

Ibid., 293.

Cf. E.P. Lumumba, Patrice Lumumba: Le Congo terre d’avenir est-il menacé (Bruxelles: Office de Publicité, S. A., Editeurs, 1961).

Ndaywei e Nziem, Histoire générale du Congo, 292.

Cf. Cornet, Les Phares verts; Adam Hochschild, King Leopold’s Ghost: A Story of Greed, Terror and Heroism in Colonial Africa (London: Pan Books, 2006).

Ndaywei e Nziem, Histoire générale du Congo, 298.

Ibid., 298–330, 409.

Cf. Armand Abel, Les musulmans noirs du Maniema (Bruxelles: Centre pour l’Etude des Problèmes du Monde Musulman Contemporain, 1959); Émile M. Braekman, Histoire du Protestantisme au Congo (Bruxelles: Editions de la Librairie des Eclaireurs Unionistes, 1961).

Théophile Kaboy, ed., Souvenirs du Centenaire et Élargissement des Connaissances sur Kasongo (Kasongo: Catholic Diocese of Kasongo, 2003).

Cf. AMAE, Dossier sur le Kitawala au Congo Belge (Bruxelles: AFI/1-6, 1956).

Information in this paragraph was obtained from Photius Koutsoukis, “Democratic Republic of Congo: Religious Groups,” December 1993, http://www.photius.com/countries/congo_democratic_republic_of_the/government/congo_democratic_republic_of_the_government_religious_groups.html.

Thomas Turner and Sandra W. Meditz, “Zaire,” Country Data, September 9, 1994, http://www.country-data.com/cgi-bin/query/r-14972.html.

Georges Nzongola-Ntalaja, “From Zaire to the Democratic Republic of Congo,” Current African Issues series, number 28 (Upsala: Nordiska Afrikainstitutet, 2004).

Dr. Gibungula Beghela visited the DRC from December 2006 to February 2007 and conducted twenty in-depth interviews with representative Muslim and Christian leaders in the eastern DRC. On the basis of the informed consent granted by the informants, none of their names are mentioned in this article, but the groups from which they were chosen are identified in footnote 25 below.

A more complex set of categories was used to analyze the interviews in Gibungula Beghela, “Vivre l’évangile de paix.” That analysis used the five-fold typology of interfaith “ideologies” developed by David Lochhead, The Dialogical Imperative: A Christian Reflection on Interfaith Encounter (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 1988): hostility, isolation, competition, partnership, and dialogue. In this article only a small selection of interviews could be used, and the attitudes have been reduced to two categories: “positive” and “negative.”

The following abbreviations are used for the religious groups selected. The informants spoke in their personal capacity, not on behalf of these religious groups:

CEU: Corps enseignant de l’Université islamique du Congo (Muslim lecturers at the Islamic University of Congo);

LMM: Leaders Musulmans de Maniema (Muslim leaders in Maniema province);

LMK: Leaders Musulmans de Kivu (Muslim leaders in Kivu province);

ECR: l’Eglise Catholique Romaine (the Roman Catholic Church);

PLEP/M: Pasteurs Leaders des Eglises Protestantes au Maniema (pastors and leaders of Protestant Churches in Maniema);

PLEP/K: Pasteurs Leaders des Eglises Protestantes au Kivu (pastors and leaders of Protestant Churches in Kivu);

AMC: Anciens Musulmans Convertis (former Muslims who have become Christians).

The marriage of a Muslim man to a non-Muslim woman is not controversial, since it is assumed in the patriarchal culture of the eastern DRC that such a woman would have to become a Muslim. When a Muslim woman wants to marry a non-Muslim man he has to become Muslim for the marriage to be approved by the family and community.

The ubuntu tradition is found across Africa and is expressed in the notion that a human being can only exist together with—and in relationship to—other human beings. Such a communal culture attaches great value to human dignity and human relationships, and both African Islam and African Christianity exist in this cultural milieu.

Laurenti Magesa, African Religion: The Moral Traditions of Abundant Life (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis, 2002).

Analetta Van Schalkwyk, “‘Sister, We Bleed and We Sing’: Women’s Stories, Christian Mission and Shalom in South Africa” (doctoral thesis, University of South Africa, 1999), 8.

J.N.J. Kritzinger, “Faith to Faith: Missiology as Encounterology,” Verbum et Ecclesia 29, no. 3 (2008): 764–90.

Cf. Louis Schweitzer, ed., Conviction et dialogue: Le dialogue interreligieux (Vaux-sur-Seine, France: Edifac, 2000).

Cf. Jacques Ellul, Violence: Reflections from a Christian Perspective (London: SCM Press, 1970).

Christian W. Troll, Dialogue and Difference: Clarity in Christian-Muslim Relations (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis, 2009).

Ellul, Violence.

Perry B. Yoder, The Meaning of Peace: Biblical Studies (Louisville, KY: Westminster/John Knox, 1992), 143.

Glen H. Stassen, Just Peacemaking: Transforming Initiatives for Justice and Peace (Louisville, KY: Westminster/John Knox, 1992), 89. See also Georg Strecker, The Sermon on the Mount: An Exegetical Commentary (Nashville, TN: Abingdon, 1988).

John Driver, Kingdom Citizens (Scottdale, PA: Herald, 1980), 68. See also Dale C. Allison, The Sermon on the Mount: Inspiring the Moral Imagination (New York: Crossroad, 1999).

N.T. Wright, Jesus and the Victory of God (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1996), 288.

Driver, Kingdom Citizens, 68.

See G.K. Beale and D.A. Carson, Commentary on the New Testament Use of the Old Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2007).

Driver, Kingdom Citizens, 68.

See also Willard M. Swartley, Covenant of Peace: The Missing Peace in New Testament Theology and Ethics (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2006).

See also Driver, Kingdom Citizens.

See also Glenn M. Penner, In the Shadow of the Cross: A Biblical Theology of Persecution and Discipleship (Bartlesville, OK: Living Sacrifice, 2004).

Walter Grundmann, Das Evangelium nach Matthäus (Berlon: Evangelische Verlagsanstalt, 1968), 176.

Grundmann, Das Evangelium nach Matthäus, 177

See also Yoder, The Meaning of Peace; and Stanley Hauerwas, Performing the Faith: Bonhoeffer and the Practice of Nonviolence (Grand Rapids, MI: Brazos, 2004).

See also Young Kee Lee, “God’s Mission in Suffering and Martyrdom,” in Suffering, Persecution and Martyrdom: Theological Reflections, eds. Christof Sauer and Richard Howell (Johannesburg, South Africa, and Bonn, Germany: AcadSA and Verlag für Kultur und Wissenshaft, 2010), 215–30.

Henri J.M. Nouwen, The Wounded Healer (New York: Image, 1979), 81 and following.

Adam Kahane, Solving Tough Problems (San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler, 2007), 83–84.

Kenneth Cragg, The Call of the Minaret (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1956), 214. Emphasis added.

David J. Bosch, Transforming Mission: Paradigm Shifts in Theology of Mission (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis, 1991), 58.

Karl-Josef Kuschel, Abraham: A Symbol of Hope for Jews, Christians and Muslims (London: SCM, 1995), 200.

Ibid., 23.

Ibid., 200–01.

See J.N.J. Kritzinger, “Interreligious Dialogue: Problems and Perspectives. A Christian Theological Approach,” Scriptura 60 (1997): 47–62; and “A Question of Mission—A Mission of Questions,” Missionalia 30, no. 1 (2002): 171, who argues that love is expressed in three basic “postures”: face-to-face; shoulder-to-shoulder, and back-to-back. He further suggests that the shoulder-to-shoulder posture is fundamental to love.

Katangole, The Sacrifice of Africa: A Political Theology of Africa (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2011), 167–68.

See http://www.giftofthegivers.org.

Miroslav Volf, Exclusion and Embrace: A Theological Exploration of Identity, Otherness, and Reconciliation (Nashville, TN: Abingdon, 1996), 75–76. “Before excluding others from our social world we drive them out, as it were, from our symbolic world” (75). This “symbolic exclusion” reveals itself in hurtful and disparaging words (“dysphemisms”) that dehumanize other people and provide justification for acts of discrimination and (eventually) physical violence against them.

Ibid., 76.

See Kritzinger, “Interreligious Dialogue,” 60.

Charles Taylor, “The Politics of Recognition,” in Multiculturalism: A Critical Reader, ed. David Theo Goldberg (Oxford: Blackwell, 1994).

Jonathan Sacks, The Dignity of Difference: How to Avoid the Clash of Civilizations (London: Continuum, 2002).

Jonathan Sacks, The Home We Build Together (London: Cromwell, 2007).

E.g., “The Oslo Declaration on Freedom of Religion or Belief,” The Oslo Coalition, 1998, accessed March 6, 2015, http://www.oslocoalition.org/oslo-declaration/.

Philemon Beghela, “Une experience d’éducation à la paix: l’Eglise Mennonite dans la region des Grands-Lacs,” Perspectives missionnaires 43, no. 1 (2002): 41–46.

The debates about the way in which religious freedoms and responsibilities are formulated in the constitution of a postcolonial African state should be traced and analyzed in depth. The work of the South African “chapter” of the World Conference on Religion and Peace (WCRP) is one of the resources that could be helpful in this regard (see, e.g., WCRP(SA), Believing in the Future [Johannesburg, South Africa: WCRP(SA), 1991]; J.N.J. Kritzinger, “A Contextual Theology of Religions,” Missionalia 20, no. 3 [1991]: 215–31). Numerous publications on religion and democratization in Africa also need to be consulted, e.g., Jeff Haynes, “Religion and Democratization in Africa,” Democratization 11, no. 4 (August 2004): 66–89.

Sacks, The House We Build.

William Storrar, “Public Anger: The Stranger’s Gift in a Global Era” (presentation, symposium on “Responsible South African Public Theology in a Global Era: Perspectives and Proposals,” Centre for Public Theology, University of Pretoria, August 4–5, 2008).

Ibid., 6.

Ibid., 22.

Storrar, “Public Anger,” 22; and William Storrar, “Public Spirit—The Global Citizen’s Gift” (presentation, symposium on “Responsible South African Public Theology in a Global Era: Perspectives and Proposals,” Centre for Public Theology, University of Pretoria, August 4–5, 2008).

E.g., Abdullahi Ahmed An-Na’im, Islam and the Secular State: Negotiating the Future of Shari’a (London: Harvard University Press, 2008); Tariq Ramadan, Islam, The West and the Challenges of Modernity (trans. Saïd Amghar; Leicester: Islamic Foundation, 2001); Tariq Ramadan, Western Muslims and the Future of Islam (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005); Tariq Ramadan, The Quest for Meaning: Developing a Philosophy of Pluralism (London: Allen & Lane, 2010).