“I feel like a refugee in my own country.”

Young Chippewayan hereditary chief George Kingfisher was addressing students at Rosthern Junior College (RJC) in Saskatchewan in April 2015.1 Elaine, as the grandchild of refugees (and a graduate of RJC), found Kingfisher’s lament particularly painful because her prairie Mennonite community has benefitted directly from the historical disenfranchisement of Kingfisher’s people.

In the last decade of the nineteenth century, the Canadian government was aggressively “opening up” prairie land to white settlers, and the Canadian Pacific railroad was facilitating new agricultural markets. A small group of families from Manitoba, Prussia, and the United States became the first Mennonite settlers in the Saskatchewan Valley in 1892, initially living in railroad cars at the line’s end in Rosthern. It was only seven years after and twenty miles from where the last battle of the Northwest Resistance had been fought at Batoche. Batoche was founded a decade earlier as a Métis settlement on the east bank of the South Saskatchewan River. It was a Francophone and Roman Catholic community, organized around a river-lot system similar to what later immigrant Mennonites had designed in Ukraine. Batoche became the center of Métis leader Louis Riel’s dissident Provisional Government of Saskatchewan, which aimed to prevent further dispossession of Métis as had occurred a few years earlier in Manitoba.2 A May 1885 battle ended the uprising; Riel and eight Indigenous men were publicly hung—the largest mass execution in Canadian history.3

Shortly after, the Department of Indian Affairs began withholding treaty payments to the Young Chippewayan band because of their alleged participation in the Northwest Rebellion. By 1888, the Department no longer identified them as a separate band. In 1898, just six years after arriving, Mennonite settlers made several requests to the government for additional tracts of land in the Saskatchewan Valley. The last of these included the Young Chippewayan Reserve that had been granted under Treaty Six (one of six numbered treaties in Saskatchewan), signed in 1876.4 The Canadian government announced that Young Chippewayans had “abandoned” their reserve and, without compensation or consultation with them, gave the land to Mennonites.5

This historic injustice remains a bone of contention today, still impacting both Mennonites and Young Chippewayans.6 It illustrates how Mennonite settlers in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries were used to “fill the prairies,” as historian Frank H. Epp put it, “to domesticate the land in the face of Indian and Métis rebellion and discourage any American intrusion.”7 Yet sociologist Leo Driedger confesses that he “grew up in the area, only thirty miles from Batoche, and had never seen the French settlement there until forty years later.” Mennonite settlers, he adds, “were often not cognizant of their role in making earlier [Indigenous and Métis] residents homeless . . . and looked upon them with disrespect and condescension.”8

This was not the first time European Mennonite settlers had displaced Indigenous communities. When Catherine the Great invited Mennonites from Prussia to farm the steppes of Ukraine in the late 1700s, traditional Nogai and Cossack peoples had been forcibly removed by the monarchy just prior to the Mennonites’ arrival.9 The same was true of the Ufa region of Russia, where the indigenous Bashkir had similarly been disenfranchised by Tsarist settlement policies—an area subsequently colonized by Mennonites (including Elaine’s great-grandparents) in the late nineteenth century.10 In both Canada and Russia, Epp summarizes, “unless permanent agricultural settlers were brought in, the nomadic native indigenous to the area . . . would make nation-building difficult if not impossible. The part which Mennonites played in the Canadian domestication program, first in Manitoba then in Saskatchewan . . . was essentialw to the national policy.”11 Leo Driedger sums up the matter: “Each time when the hunters and trappers had been cleared away, the Mennonites moved in. It was a struggle between the food gatherers and the food growers—the hunters and the farmers. The Mennonites were part of the farming invasion.”12

In his essay exploring these issues almost a half century ago, Driedger concludes poignantly: “As a minority concerned about love and their neighbors, could [Mennonites] participate in the agricultural invasion of another minority which destroyed the livelihood and way of life of that minority, without serious compromise of their beliefs?”13 This question still hovers over Elaine’s community, intensified by contemporary movements of decolonization and Indigenous Resurgence in which many Anabaptists seek to participate.14

Below we offer two biblical reflections to help us reset our compasses concerning our conflicted past and present, and our aspirations to embrace a decolonizing discipleship.

- “Killing and Taking Possession”: Colonization vs. Nahala (I Kings 21)

The story of Naboth is an old one, but it is repeated every day.

—St. Ambrose, De Nabuthae

The penultimate chapter of First Kings is a relatively free-standing narrative unit inserted into the Deuteronomic history of the Omrid dynasty. The canonical placement of the story suggests its ancient standing as an important cautionary tale from the Elijah cycle. The story pits the famously apostate Israelite King Ahab and Jezebel, his Sidonian Queen, against the traditional landowner and protagonist Naboth. Hebrew Bible scholar Ellen Davis rightly calls this “an emblematic tale of two economic systems or cultures in conflict, each with a different principle of land tenure.”15 Most contemporary readers, socialized into the culture of real estate deals and state rights of eminent domain, see no problem with Ahab’s proposition: from a settler vantage point, the king appears to make a generous offer (v. 2), while Naboth’s unequivocal refusal seems unreasonable (v. 3). Yet from the perspective of indigeneity, the struggle between Naboth’s ancestral land-stewardship and Ahab’s royal land-grab represents a perennial and vastly asymmetrical contest, portrayed here as a grim parody.

The setting is germane (v. 1): the Jezreel Valley was then (and still is today) the agricultural heartland of Israel. Ahab’s abode is a “palace”—a term the Bible usually reserves for foreign kings—and this is only his winter residence. Naboth, on the other hand, is from the traditional agrarian class; the key to understanding his perspective lies in the Hebrew term nahala (v. 3). Typically but poorly translated as “possession” or “inheritance,” the word rather connotes a sense of ancestral stewardship of land understood as a gift from the Creator, its use contingent upon an intergenerationally enduring Covenant relationship. Tellingly, there is no appropriate word in English that expresses such a meaning, our semantic system having developed alongside the rise of capitalism. Our attitudes toward land—long shaped by ideologies of ownership and “productivity” defined by profit—make it difficult for us to comprehend nahala as a relationship completely free of commodification.

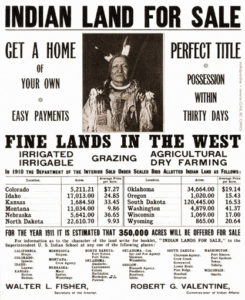

The only line Naboth speaks in the entire story articulates concisely an indigenous cosmology: The land does not belong to him, he belongs to it (v. 3). Davis points out that Naboth’s objection is predicated on the theological notion of impurity (halila): to sell the land would defile him. In a few strokes, the biblical storyteller has captured the incommensurable difference between two ways of life that has defined the history of civilization. It narrates the essential conflict between an aggressive political-legal culture based upon an ideology of land possession versus one in which there is no word for land ownership. The former prevails historically by force of arms, followed by economic and legal appropriation, from Ahab to Canadian and American settler states—depicted summarily in a 1911 United States Department of the Interior advertisement (seen on next page).16

The social context of the biblical tale was the expanding power of the Omrid regime, which brought an intensification of land expropriation and centralized command economics to early Iron Age Israel. Ahab (who reigned from ca. 870 to 850 BCE) aligned by marriage with nearby Canaanite city states—thus, the narrative’s “casting of Phoenician Jezebel as villainess.”17 Their “foreign and domestic policies . . . were enriching for the elite but difficult or disastrous for small farmers,” and “required the appropriation and redistribution of food commodities on a large scale, and thus the conversion of Israel’s economy from one focused on local subsistence to a state-controlled economy designed to generate surpluses of the key crops.”18 Traditional smallholders were compelled to grow for export in a system controlled by royal managers or were forced off the land by debt or tribute burdens. The result was a disenfranchisement of traditional subsistence agriculture, the destruction of village life, a rising disparity of wealth, and the degradation of local ecosystems. These impacts are all too familiar to native people in modernity, not least contemporary Cree communities facing Canadian Tar Sands extraction.19

The rise of socioeconomic disparity in ancient Israel provoked two waves of prophetic protest: Elijah and Elisha in the ninth century BCE and Amos, Hosea, Isaiah, and Micah in the eighth. They railed against the ruling class while reasserting Sabbath covenants to try to preserve the old agrarian system of mutual aid and equity in the face of elite “structural adjustments.”20 The Naboth legend lies at the roots of this prophetic tradition of advocacy for land justice.

The plot commences with an account of the sinister royal conspiracy to seize what Naboth refuses to sell or trade (vv. 4–16). This was not only a provincial dispute over eminent domain but also a political power play through which Ahab attempted to break agrarian pockets of resistance to his growing royal hegemony.21 It may have been why he moved his winter palace into the Jezreel valley (21:1)—not unlike putting a US fort in the heart of Indian Territory in the nineteenth century, or a US military base in the middle of tribal areas of Afghanistan today. The ancient tale captures the continuing story of empire: resources that can’t be accessed by persuasion (or market seduction) will be taken by covert or overt political force.

The recalcitrant Naboth refuses to sell out, a stance recounted three times by his incredulous and outraged antagonists (vv. 4, 6, 13). Unable to co-opt him, the regime sets about eliminating him. Jezebel now becomes the main actor in a sordid plot, while Ahab is portrayed as a sulking little boy who can’t get what he wants. “Are you exercising sovereignty or not?” she taunts (paraphrasing v. 7). This unflattering portrait has all the elements of a political cartoon, since, in fact, Ahab was a powerful warrior and stern ruler who lost few battles and brooked no opposition. The Bible is full of such political satire and dark caricature, traditionally a powerful rhetorical weapon of the disenfranchised.22 Jezebel’s underhanded dealings are, for example, echoed later in the Gospel satire of a drunken Herod conscripting women to help murder the inconvenient prophet John the Baptist (Mk 6:17–28), and again in Jesus’s trial before the Jerusalem authorities, convicted by false witnesses. 23

The Phoenician Queen—agent of the nearby powerful and aggressive city states of Tyre and Sidon—knows how to break native resistance. Naboth is brought up on trumped-up charges, in which his defiance is characterized as a “curse” on the King (vv. 8–10).24 The local village assembly of elders, of which Naboth is a member, is turned against him, doubtless by granting favors to those who cooperate with the conspiracy. This too is part of the archetypal story: divide, then conquer. But in the end, of course, local leaders who collaborate with the regime so as not to share Naboth’s fate will lose their way of life too.

The narrative depicts the worst kind of political and moral behavior. The plot to murder an innocent man is

- veiled in the piety of a public fast;

- engineered by false witnesses (perhaps the worst sin in Torah); and

- couched in terms of blasphemy against God and the king—as if the two were equivalent!

The despicable plan—which makes a mockery of sacred ritual, community deliberation, and theological confession all at once—is carried out, the careful repetition of each detail meant to underline its depravity (vv. 11–13). The depressing finality of Naboth’s demise and foreclosure of land is then again reiterated three times (vv. 14–16).

But just as the king is about to take legal possession of Naboth’s land, Elijah’s intervention opens a new chapter in the resistance (vv. 17ff). The wilderness prophet has already skirmished repeatedly with Ahab (I Kg 17–19), and Elijah has gone into hiding for fear of his life (I Kg 18:3–4). Moreover, Jezebel, already described by the narrator as a killer of the prophets of Israel, has a standing vendetta against Elijah (19:1–2). But despite the obvious dangers of confronting these rulers with their public crimes, their assault on the traditional way of life in Jezreel is so egregious that the beleaguered prophet again rousts himself to speak truth to power.

Elijah pronounces the divine double indictment (21:19) on Ahab’s strategy. Murder and expropriation—repeated three times in succession in verses 15, 16, and 19—is the most concise definition of settler colonialism’s crimes across history. The king rightly understands the prophet to be his enemy: “Ah, you again!” he laments wearily (cf. v. 20a). Elijah’s retort is sharply ironic: The one whose land policies are creating debt slaves across the latifundialized economic landscape has sold himself into slavery—presumably to his Phoenician overlords (v. 20b). The eventual result of oppressive politics will be reciprocal violence, because the power of death is contagious. Elijah goes on to describe the murderer’s fate in graphic detail (vv. 21–24).

The epilogue to the tale is also instructive to settler readers. After reiterating that “there was no one like Ahab, who sold himself to do what was evil” (v. 25, NRSV), the narrator reports Ahab’s surprising response to Elijah’s indictment: the king “tore his clothes and put sackcloth over his bare flesh[, and] fasted” (v. 27). Is this unlikely repentance part of the political cartoon? This depends on how we interpret God’s explanation to Elijah, which closes the narrative: “Have you seen how Ahab has humbled himself before me? Because he has . . . I will not bring the disaster in his days; but in his son’s days I will bring the disaster on his house” (v. 29). It articulates an important dialectal realism we often find in biblical narratives: personal efforts to “turn around” are meaningful, even among the powerful—but by themselves they do not change political systems. Ahab’s penitence—notably, there is no mention of any change in Jezebel’s imperial character—can at most only postpone the collapse of his regime, something his unsustainable policies make inevitable. As narrated later in II Kings 9, the Omrid dynasty indeed expires in the next generation.25 As for Jezebel, her sons bleed to death on the very ground of Naboth’s vineyard, and the Queen herself is thrown out of a palace window by her own attendants (another cartoon; II Kg 9:30–37). The violence of imperial “murder and dispossession” ultimately also consumes its perpetrators: divine judgment as historical consequence.

A millennium later, Saint Ambrose, the Archbishop of Milan, invoked Naboth’s legacy to protest injustice in the late Roman Empire. De Nabuthae was written in the last decades of the fourth century CE, just a few generations after the Christian church had made its fateful deal with Constantine, after which she would be colonized almost beyond recognition. Its opening lines are a lament echoing down the corridor of ages, as if Ambrose was summarizing the countless acts of genocide and dispossession that empires had inflicted and would continue inflicting on people of the land:

The story of Naboth is an old one, but it is repeated every day. Who among the rich does not daily covet others’ goods? Who among the wealthy does not make every effort to drive the poor person out from his little plot and turn the needy out from the boundaries of his ancestral fields? Who is satisfied with what is his? What rich person’s thoughts are not preoccupied with his neighbor’s possessions? It is not one Ahab who was born, therefore, but—what is worse—Ahab is born every day, and never does he die as far as this world is concerned. For each one who dies there are many others who rise up; there are more who steal property than who lose it. It is not one poor man, Naboth, who was slain; every day Naboth is struck down, every day the poor man is slain.26

Another millennium and a half later, the biblical warning tale was invoked again by Hawaiian Queen Lili’uokalani. In an open letter to the American people—penned under house arrest in 1898 after the US government, in cahoots with local settler plantation owners and militias, had overthrown her traditional rule and annexed the island nation—the Indigenous and devoutly Christian leader Lili’uokalani appealed to American conscience:

Oh honest Americans, as Christians hear me for my downtrodden people! . . . Quite as warmly as you love your country, so they love theirs. With all your goodly possessions, covering a territory so immense that there yet remain parts unexplored . . . do not covet the little vineyard of Naboth’s, so far from your shores, lest the punishment of Ahab fall upon you, if not in your day, in that of your children.27

Lili’uokalani’s plea fell on deaf ears.28 Indeed, Ambrose’s indictment pertains to “every day” of the US history of settler colonialism.

The searing testimonies of both Ambrose and Lili’uokalani confirm the biblical story as an enduring warning parable about all who “kill” traditional people and “take possession” of their nahala. Yet, it has rarely been heeded in the history of Christian missions since Columbus. That legacy hangs heavily over settlers who would decolonize our discipleship—which brings us to a long-ignored passage from the New Testament.

- Christian Mission “Disrobed”: The Road Not Taken (Luke 9:1–6)

When the Missionaries arrived, we natives had the land and they had the Bible. They taught us how to pray with our eyes closed. When we opened them, they had the land and we had the Bible. —Jomo Kenyatta 29

Most would-be “progressive” Christians today, including Mennonites, prefer to disassociate from the painful, half-millennium-long history of entanglement of missions with colonization. But we cannot be exonerated by such a “move to innocence.”30 Regardless of whether or not one calls oneself a Christian today, our society was fundamentally shaped by the collusion between churches and empire—and our settler race, class, and gender privileges are rooted in this legacy. Decolonization requires that we face this history, in order to embrace the demanding work of restorative justice and healing.

Jesus’s so-called “Missionary Instructions” as recorded in Luke’s Gospel should haunt the conscience of Christendom. Their essence is: “Whichever house you enter, stay there, and leave from there” (Lk 9:4). Had Christians observed these straightforward guidelines for how to live among other peoples and places, the history of the world would be profoundly different. Jesus could not have been clearer or more unequivocal in his marching orders, as we’ll overview below; but for the most part, our ancestors in the faith ignored them. Consequently, a bitter legacy of domination and genocide has been tattooed on the centuries and on every land around this wide world.

Obviously Christian missions have a long and complex history, so we want to make four preliminary observations:

1.First, it is important to acknowledge that the spread of Christianity across time (two millennia), space (the entire globe) and cultures (almost none untouched) hasn’t always and everywhere been synonymous with colonization. If we assume a simplistic, single story we miss significant episodes in which the gospel spread organically and peaceably, and often not through the agency of white folk.

2.Second, it is equally crucial to recognize that, all too ubiquitously over the past five hundred years, Christian missions has fused cross and sword, conversion and conquest, evangelization and subjugation. Because of this apostasy, the history of contact between Indigenous and settler cultures in the Americas has been fraught, right to the present day.

3.Third, we should recognize that Christianity has, from its beginnings, been mission-driven. The first disciples took up Jesus’s annunciation of God’s kingdom as an alternative to the Roman Empire, as a vision of grace, social equality, mutual aid, and healing. This message of liberation and wholeness spread rapidly among those who suffered under the oppressive social order of Rome’s slave-based, extractive economy. It was a subversive mission with real social costs, as reflected in Luke’s portrait of the Apostle Paul in Acts, who confesses: “The Holy Spirit testifies to me in every city that imprisonment and persecutions are waiting for me. But I do not count my life of any value to myself, if only I may finish my course and the ministry that I received from the Lord Jesus, to testify to the good news of God’s grace” (Acts 20:23–24).

- The Jesus movement’s use of the trope “good news” (Greek euangelion), appropriated from the lexicon of Roman propaganda, was polemical and pointedly political. Caesar’s public relations machine boasted that the Pax Romanahad brought euangelia to the world, for which every city in the Eastern Empire had to keep a festival at which sacrifices were offered on behalf of the Emperor’s “grace.” Imperial media proclaimed this myth everywhere, including on everyday coins, such as the denarius circulating in Palestine (right).31 The goddess Providentiaholds a globe in her right hand, symbolizing world-sovereignty; the Latin inscription boasts AETERNITAS—Rome’s hegemony forever. The early church’s counter-euangelion challenged this political cosmology, announcing the restoration of God’s sovereignty through Christ the “Lord” (Caesar’s title). Picking a fight in this war of myths is why evangelists like Paul landed in jail.

- After the adoption of Christianity by Emperor Constantine in the fourth century CE, what began as a grassroots mission from belowfor liberation from empire became increasingly a project of imperial conquest from above in the name of the church.32 A millennium later, in late medieval Europe, Christendom’s mission of hegemonic expansion began to be fused with powerful mythologies of ethnic superiority, codified in papal pronuncimientos that articulated a Doctrine of Discovery.33 Of the many white supremacist conceits that followed, perhaps none was more consequential than the notion that the European’s arrival on other shores represented a religious epiphany—of “enlightenment” for “pagan” inhabitants and of entitlement for Christian subjugators.34 This ideology drove five hundred years of missions-as-conquest, leaving no corner of the world untouched. Modern churches, including Mennonite, have yet to come to terms fully with this history—though some denominations over the past half-century have declared a “missions moratorium.”35

4.Fourth, we must acknowledge that Christianity is not uniquely missionary. Many social movements throughout history have been equally aggressive in spreading their message, including secular ones (we might think of the Communist movement over the past century, or US wartime propaganda mobilizing prejudice and xenophobia in order to recruit civilians to become soldiers).

- If ancient Roman propaganda functioned as imperial “good news,” so too did the powerful nineteenth-century American ideology of Manifest Destiny. Images such as the famous one on the next page certainly motivated settlers to “convert” the continent to their vision.36 Originally produced for a railroad recruiting poster shortly after completion of the US transcontinental railroad in 1869, John Gast’s painting sought to assure whites in the east that it was “safe” to move to the far west. The foreground unabashedly celebrates an inexorable march of white domination across the continent, tellingly led by militia, followed closely by resource extractors and then farmers. Westward-moving (aimed at the Pacific, far upper right) transportation dominates the middle of the composition: a covered wagon, Pony Express rider, stagecoach, and two locomotives (while ships ply the Mississippi River at right). The sun rises behind them, as Indigenous people, together with buffalo and bear, flee into the darkness (left). The symbolism is firmly secular: that’s not an angel at the center of the painting but the mythic image of “Columbia” (the feminized version of Columbus), presented as the goddess of liberty and the personification of America. She lays telegraph wire with her left hand, and in her right is a School Book (not the Bible)! Such settler art narrating conquest and colonization was ubiquitous in the nineteenth century and still adorns many public buildings around the United States today.37

- Our point here is that powerful social movements are usually missionary, for good and for ill. Today US corporations roam the globe in search of resources to extract and markets to dominate, evangelistically promising economic growth and capitalist “fixes” to social problems. One could argue that the archetypal twenty-first century American businessperson traveling abroad has fewer scruples about exploiting people and land than the most ethnocentric nineteenth-century Christian missionary! Mission is perhaps better defined generically, then, as convictional and critical engagement with the world by those with a vibrant vision of an alternative. The critical ethical questions are: Mission for what? Howis the mission embodied? With whom and where? And, most importantly, to whose benefit?

- For any mission-driven cause—whether religious or secular—pressinga critique and a “good news” alternative is one thing. Imposing a problem analysis and its solution—especially by military, or economic or cultural force—is quite another. The challenge is how mission-driven movements can remain structurally and ideologically free of the politics of domination. And the ancient key, according to Jesus’s original missionary instructions, is the ethos of hospitality—given and received.

The perverted gospel of colonization was, and is, founded upon a colonization of the gospel—that is, the (often theologically elaborate) ways that churches ignore, suppress, or rationalize away the clear directives Jesus gave his followers regarding their missionary vocation. As is so often the case, the roots of our tradition reveal where Christians went so wrong. Luke underlines the importance of Jesus’s missionary marching orders by reporting them twice: in chapter nine (sending out the Twelve) and again in chapter ten (sending out the Seventy). The latter is more elaborate; we’ll examine the shorter version. It is laid out here as a chiasm:

Jesus called the twelve together and gave them power and authority over all demons and to cure diseases, and sent them out to proclaim the kingdom of God and to heal.

He said to them, “Take nothing for your journey, no staff, nor bag, nor bread, nor money—not even an extra tunic.

Whatever house you enter, stay there, and leave from there.

Wherever they do not welcome you, as you are leaving that town shake the dust off your feet as a testimony against them.”

They departed and went through the villages, bringing the good news and curing diseases everywhere.

—Luke 9:1–6 (NRS)

We identify the following salient points in light of the critical questions posed above.

What: The purpose of Jesus’s gospel mission is twofold. Disciples are “empowered” to

i.proclaim an alternative sociopolitical order called the kingdom of God; and

ii.heal (Greek therapeuein) people oppressed by the demonic and by disease.

Each practice is iterated in verses 1 and 6, framing the passage for emphasis, and identified as “good news.” Given that in every human society one can identify elements of both political oppression and personal illness, a mission that advocates for freedom, justice, and health would seem to resonate with universal moral values.

How: The significance of the first instruction (9:3) cannot be overstated: to paraphrase, “Don’t carry your baggage into your host community.” This is not just about traveling light; it’s about going vulnerably. Forbidding staff and bag means missionaries are to be liminal, which is to say not in control. Jesus’s strategy alludes, by way of contrast, to the old story of David, who famously approached the foreigner Goliath with a staff and a bag full of five stones—in other words, to do battle (I Sam 17:40). Too often in post-Columbian Western history, missionary baggage was weaponized because the ultimate goal was not liberation but domination; not to heal but to usurp. Similarly, Jesus’s directive to travel without bread and money refers to the means of sustenance on the road. Not to be self-sufficient renders missionaries dependent upon those they approach. This ensures that the host, not the guest, retains the upper hand.

The counsel to possess only one tunic is interesting. A “change of clothes” would have been a rare luxury among peasant Middle Easterners. Moreover, Luke’s John the Baptist had exhorted at the outset of this story: “Whoever has two coats must share with anyone who has none” (Luke 3:11). Presumably, Jesus is here ensuring that missionaries have already distributed their surplus. We might further extrapolate that a limited wardrobe means that eventually missionaries will have to adopt the local style of dress! Indeed, costumes matter; they are a way of either fitting in or remaining apart, of cultural imposition or of adaptation. European Christian missionaries almost always got this exactly backward.

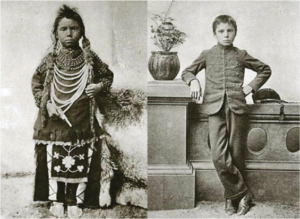

Not only did they bring trunks full of their own culture but they also forced this baggage (including their European costumes) on their native hosts (as in the well-known image above).38 How different things would have been had Christians practiced a “disrobed” mission—naked, so to speak, and unashamed.

With whom and where: The second of Jesus’s three instructions concern the missionary’s responses toward “welcoming” homes (9:4). We should note that the phrase “whatever house you enter” (Greek heis ēn an oikian eiselthēte, an aorist subjunctive active second person plural) connotes a conditional or contingent prospect—a welcome cannot be assumed, much less demanded. Jesus then underlines two crucial and contrasting imperatives regarding the guest’s “positionality”:

- “stay there . . .” (ekei menete, meaning to “remain, abide, or continue on”)

- “. . . and leave from there” (exerchesthe, an imperative present middle or passive deponent second person plural, which could be translated “and be gone from there”)

This is expanded in Luke’s longer version: “Remain in the same house, eating and drinking whatever they provide. . . . Do not move about from house to house. Whenever you enter a town and its people welcome you, eat what is set before you” (10:7–8). In other words, don’t look for a better deal, don’t demand special treatment, eat locally and gratefully (reiterated twice).

The idea here seems to be that the missionary remains a guest with the task of understanding the new place and people, which can take a very long time. Being “hosted” is the opposite of colonizing “settlement,” because eventually the missionary leaves. That these instructions were taken seriously in the early apostolic movement is indicated by the narratives of Paul’s missionary itineration in both Acts and his own epistles. And should the missionary be invited to stay permanently—though, interestingly, Jesus does not include this prospect, nor did Paul “settle” in the communities he missionized—it is on the terms of the host. The missionary’s tenure as guest presumably trains them how to enculturate into their host’s way of life and how to let the Good News indigenize.

All of this is predicated, however, on finding locals willing to provide more than “passing through” hospitality. Jesus realistically assumes there will be places where this is not the case (9:5). Because this is always and everywhere a distinct possibility, a final simple instruction is included: If you are unwelcome, leave. Don’t retaliate, don’t force yourself on the locals, and don’t take over their country! Move on. The ritual of shaking off the dust from one’s feet is clearly a symbolic gesture that is important to Luke, since it also appears several times in Acts.39 In Luke 10:11 Jesus elaborates it as a form of protest, associating it with Sodom, whose primal sin (contrary to how most Christians understand that old tale) was lack of hospitality to strangers.40 This confirms inhospitality as a serious problem, especially for missionaries. But all one can do is point it out. If people or societies don’t have ears to hear Good News—providing of course that the missionary’s telling and showing of the gospel is credible and respectful—then try elsewhere. Done and dusted, as it were.

The truth is, European missionaries in the New World almost always initially encountered generous hospitality from Indigenous peoples they met, since welcoming strangers was and is endemic to native cultures. Roger Epp points out that settler societies in North America were “founded on an act of sharing that is almost unimaginable in its generosity”41 “—not only land, but food, agricultural techniques, practical knowledge, and trade routes,” including treaty-making.42 But this hospitality was very soon abused by the guests, who, as “double agents” of both church and colonial powers, pursued objectives more suited to conquest and settlement than to community and respectful coexistence.

At the center of the chiastic structure (bolded above) of Jesus’s teaching in Luke 9:1–6 is the command to respect one’s host by learning how to live within the limits of their capacity for (and willingness to extend) hospitality, and knowing when to leave. How different history would have been had Christians practiced “unsettling” styles of mission—embodying the Good News of healing and liberation, and moving on. Instead, we are haunted by the oft-repeated lament of African leader Jomo Kenyatta cited at the beginning of this section. Our missionary forebears too often promoted (or tolerated) “Jezebelian” policies of “killing and taking possession.”

***********

Both the radical teaching of Jesus—the road not taken by our missionary predecessors in the faith—and the ghost of Naboth from our deep religious past, ought to still trouble North American Christians, including Mennonite descendants of the “agricultural invasion.” The virulent legacy of colonizing missions explains why so many justice-seeking people today—Indigenous and others—have shaken the dust from their feet in protest of our tradition. The future of gospel mission depends upon whether we will be accountable to—not evasive of—this dysfunctional inheritance, and work to heal it through practices of restorative solidarity and reparation.

Can we settler Christians reimagine a “disrobed” and “unsettling” style of mission focused only on healing and liberation—and on solidarity with Indigenous people? Or will our efforts seem too little and too late in a world facing ultimatums of climate catastrophe, viral pandemics, and racial inequities that affect the poor first and worst? The good news at the roots of our faith holds that new beginnings are possible when we abandon our civilizational presumptions. Jesus’s call still bids us to “repent”—that is, to “turn around” our personal and political histories—in order to embrace the hospitality of God, here and now (Mk 1:14–15).

The soul of Jezebel surely inhabits many of our rulers today: bulldozing oil pipelines over the bodies of Water Protectors at Standing Rock, and engineering coups in places like Bolivia for resources like lithium, determined to colonize the remotest reaches of Creation. But the voice of Elijah lives too, challenging the children of settler colonialism to make things right—or face the inevitable consequences. Indeed, Elijah, like Jesus, is notoriously “undead” in the biblical testimony. His legacy hovers over our history in a fiery chariot like an unresolved chord (see II Kg 2), beckoning us to speak truth to the Ahabs within and around us and to stand with Naboth’s spiritual “kin” in the ongoing struggle for justice and repatriation. It was this Elijah that Jesus summoned to witness as he hung upon a Roman cross (Mk 15:35). And in his resurrection, the Nazarene similarly carries on his gospel insurrection, despite empire’s attempts to disappear it.

The only way to resolve the double haunting of these two prophets is to take up their mantle, as did Elisha (II Kg 2:13–15) and the early Jesus followers (Mk 1:16–20). May we keep alive their tradition of healing mission in our decolonizing discipleship, and thereby also forge a future for Anabaptist faith and practice.

Elaine Enns (a restorative justice educator) and Ched Myers (an activist theologian) are partners, Mennonites, and codirectors of Bartimaeus Cooperative Ministries on unceded Chumash territory in the Ventura River Watershed of Southern California. In 2009 they coauthored Ambassadors of Reconciliation, Vols I & II: New Testament Reflections and Diverse Practices of Restorative Justice and Peacemaking (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis, 2009). To learn more about their work, see https://www.bcm-net.org/ and https://www.chedmyers.org/.

This piece is an edited excerpt from the “Theological Interlude” portion of Elaine Enns and Ched Myers’ forthcoming book Healing Haunted Histories: A Settler Discipleship of Decolonization (Eugene, OR: Cascade, 2020).

Footnotes

Donna Schulz, “Students Learn about Indigenous Land Issues: RJC Benefitted from Injustices to Young Chippewayan First Nation,” Canadian Mennonite online, May 20, 2015, http://www.canadianmennonite.org/stories/students-learn-about-indigenous-land-issues.

In 1867, British Colonial control of Canada stretched only as far west as Ontario; nothing north and west had been surveyed. Many Métis had settled in the Red River area outside present-day Winnipeg, but in 1870 their land was unilaterally transferred to the Canadian government, sparking a rebellion led by Riel. Through negotiation, Manitoba became a province under Canadian confederation, but, still disenfranchised, many Métis moved farther west to Saskatchewan, where they tried again to assert their nationality under Riel. The Northwest Resistance of 1885 “began as a peaceful citizen’s protest against government inefficiency” but ended in tragedy, for which the “federal government must bear most of the responsibility” (Gerald Friesen, The Canadian Prairies: A History [Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1987], 228).

The Saskatchewan Indian newspaper reported: “All the Indian students at the Battleford Industrial School were taken out to witness the [hangings] . . . to remind them what would happen if one of them made trouble with the crown” (quoted in Tamara Starblanket, Suffer the Little Children: Genocide, Indigenous Nations and the Canadian State [Atlanta: Clarity, 2018], 118). See Arden Ogg, “An Infamous Anniversary: 130 Years Since Canada’s Largest Mass Hanging,” Cree Literacy Network (November 26, 2015). See also the historical summary at Canadian Geographic Indigenous Peoples Atlas of Canada, https://indigenouspeoplesatlasofcanada.ca/article/1885-northwest-resistance/.

Doreen Guenter, ed., Hague–Osler Mennonite Reserve, 1895–1995 (Saskatoon: Hague-Osler Reserve Book Committee, 1995), 29.

“I can remember as if it happened yesterday when we left our reserve,” said Albert Snake in an interview with Harry Michael in February 1955. “I was about nine years old when my grandfather Chippewayan, the chief, advised his people to leave their reserve for the winter . . . because he was afraid they would have nothing to eat. . . . They were not getting provisions as promised by the treaty. . . . My grandfather waited for all this, and there was no sign of any coming when we left our reserve.” In 1972, Snake, as Chief of the Young Chippewayan band, requested Canada’s Minister of the Interior to review their land claim, to no avail (in Leonard Doell Archives, Saskatchewan). See further, Doell, “Young Chippewayan Indian Reserve No.107 and Mennonite Farmers in Saskatchewan,” Journal of Mennonite Studies 19 (2001): 165–67.

Summarized in the 2016 documentary directed by Brad Leitch—Reserve 107: Reconciliation on the Prairies, produced by Rebel Sky Media, https://www.reserve107thefilm.com/.

Frank H. Epp, Mennonites in Canada 1786-1920: The History of a Separate People, vol. 1 (Toronto: Macmillan of Canada, 1974), 209, 305.

Leo Driedger, “Native Rebellion and Mennonite Invasion: An Examination of Two Canadian River Valleys.” Mennonite Quarterly Review 46 (July 1972): 299.

See James Urry, None but the Saints: The Transformation of Mennonite Life in Russia 1789–1889 (Kitchener: Pandora, 1989), 96, 107.

See N. J. Neufeld et al., Ufa: The Mennonite Settlements (Colonies) 1894–1938 (Steinbach, MB: Derksen Printers, 1977), 20.

Epp, Mennonites in Canada 1786–1920, 305.

Leo Driedger, “Louis Riel and the Mennonite Invasion,” Canadian Mennonite, XVIII (Aug 28, 1970): 6.

Leo Driedger, “Native Rebellion and Mennonite Invasion: An Examination of Two Canadian River Valleys,” Mennonite Quarterly Review 46 (1972): 300.

“Indigenous Resurgence” is a concept defined and popularized by Mohawk educator and activist Gerald Taiaiake Alfred (see Taiaiake Alfred, “Don’t Just Resist. Return to Who You Are,” Yes! Online, April 9, 2018, https://www.yesmagazine.org/issue/decolonize/2018/04/09/dont-just-resist-return-to-who-you-are/). See also Leanne Betasamosake Simpson, “Indigenous Resurgence and Co-resistance,” Critical Ethnic Studies 2, no. 2 (Fall 2016): 19–34; and Gerald Taiaiake Alfred, “Indigenous Resurgence,” Intercontinental Cry, March 29, 2009, Simon Ortiz and Labriola Centre Lecture series, https://intercontinentalcry.org/indigenous-resurgence-of-traditional-ways-of-being/.

Ellen F. Davis, Scripture, Culture, and Agriculture: An Agrarian Reading of the Bible (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008), 111.

The portrait in the poster is of Not Afraid of Pawnee (Yankton Sioux tribe); the flyer indicates the average prices of tribal lands per acre (image at California Indian Education, http://www.californiaindianeducation.org/indian_land/for_sale/).

Tamis Hoover Rentería, “The Elijah/Elisha Stories: A Socio-cultural Analysis of Prophets and People in Ninth-Century B.C.E. Israel,” in Elijah and Elisha in Socioliterary Perspective, ed. Robert B. Coote (Atlanta: Scholars, 1992), 91.

Davis, Scripture, Culture, and Agriculture, 113.

See, for example, “Tar Sands,” Indigenous Environmental Network,” https://www.ienearth.org/what-we-do/tar-sands/.

For a popular summary account, see Ched Myers, The Biblical Vision of Sabbath Economics (Washington, DC: Tell the Word, 2001), 10–22.

Davis (Scripture, Culture, and Agriculture, 112) suggests that Ahab’s “vegetable garden” (21:2) was a ruse; his aim was “to appropriate [Naboth’s vineyard] and produce wine, first for his own table and then for the export economy.” Lavish displays of wealth were strategies through which elites maintained power, formed political alliances, and bought off potential opponents.

On parody as a subversive strategy of the oppressed, see James C. Scott, Weapons of the Weak: Everyday Forms of Peasant Resistance (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1987), 137–57. Also Ze’ev Weisman, Political Satire in the Bible (Atlanta, GA: Scholars, 1998).

See Ched Myers, Binding the Strong Man: A Political Reading of Mark’s Story of Jesus (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis, 1988/2008), 214–14, 369–80.

This is because Naboth allegedly “reneged on a deal,” according to Judith Todd, “The Pre-Deuteronomistic Elijah Cycle,” in Elijah and Elisha in Socioliterary Perspective, ed. Robert B. Coote (Atlanta, GA: Scholars, 1992), 33. All Scripture citations are from the New Revised Standard Version.

For a summary of conflicting archaeological evidence and historical timelines concerning the Omrid dynasty, see “Omrides,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Omrides.

Full text can be found at “On Naboth,” Hymns and Chants, https://hymnsandchants.com/Texts/Sermons/Ambrose/OnNaboth.htm.

Lili’uokalani (Queen of Hawaii), Hawaii’s Story by Hawaii’s Queen (Boston: Lee and Shepard, 1898), 373. These words close her lengthy memoir detailing her unjust overthrow. See https://digital.library.upenn.edu/women/liliuokalani/hawaii/hawaii.html.

For accounts of the American coup, see https://hawaiiankingdom.org/blog/the-1887-bayonet-constitution-the-beginning-of-the-insurgency/ and Michael Dougherty, To Steal a Kingdom: Probing Hawaiian History (Honolulu: Island Style), 2000.

An adage often attributed to Desmond Tutu, Kenyatta’s lament was reported in John Frederick Walker’s A Certain Curve of Horn: The Hundred-Year Quest for the Giant Sable Antelope of Angola (New York: Grove, 2004), 144. It may also have origins in Chinua Achebe’s 1958 novel Things Fall Apart (New York: Penguin, 1994).

“Moves to innocence” are settler strategies for dodging historical complicity as outlined by Indigenous scholar Eve Tuck and Wayne Yang in their seminal essay “Decolonization is Not a Metaphor,” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education and Society 1, no. 1, (2012): 1–40.

Image at “Diva Faustina AETERNITAS from Rome,” Victor Imperial Coins, https://www.vcoins.com/en/stores/victors_imperial_coins/208/product/diva_faustina_aeternitas_from_rome/1045839/Default.aspx.

See, for example, Charles Odahl, Constantine and the Christian Empire (Philadelphia: Routledge, 2005).

For important historical background, see Ronald Sanders, Lost Tribes and Promised Lands: The Origins of American Racism (Westland, MI: Perennial, 1992) and Steve Newcomb, Pagans in the Promised Land: Decoding the Doctrine of Christian Discovery (Golden, CO: Fulcrum, 2008). Mennonite resources for education and advocacy are at “Dismantling the Doctrine of Discovery: A Movement of Anabaptist People of Faith,” https://dofdmenno.org/ and “Doctrine of Discovery,” Mennonite Church USA Resources, http://mennoniteusa.org/resources/doctrine-of-discovery/.

This is archetypally captured in Joshua Shaw’s Manifest Destiny-era painting “Coming of the White Man” (1850, https://www.csub.edu/~gsantos/img0105.html). The painting depicts Indigenous people blinded by and cowering before a sunrise that brings a European tall ship from the east; above them fly geese (symbolizing “naturalistic” migration patterns).

Both the global decolonization movement of the mid-twentieth century and the growing indigenization of many Third World churches led some mainline North Atlantic Protestant denominations to rethink the missionary legacy and vocation; in the early 1970s, the World Council of Churches (WCC) called for the moratorium. As Fr. Paul Verghese, an East Indian theologian and former associate general secretary of the WCC, put it in 1974: “Today it is economic imperialism or neo-colonialism that is the pattern of missions,” which he called “the greatest enemy of the gospel” (quoted in Rob Goodwin, Eclipse in Mission: Dispelling the Shadow of Our Idols [Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock, 2012], 7). The missions moratorium caused yet another split between First World mainstream denominations and evangelicals for whom soul-winning remains the raison d’ȇtre of the faith.

Image found at “American Progress,” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/American_Progress.

Our colleague Jim Bear Jacobs has long drawn attention to the racist nature of murals at the Minnesota State Capitol (see “Public Art,” Healing Minnesota Stories: Working toward Understanding and Healing between Native American and Non-Native Peoples, https://healingmnstories.wordpress.com/capitol-art/). Similarly, a statue of Columbus and Queen Isabella in the middle of the Rotunda at the California State Capitol was the target of native activists in 2018 in a Poor Peoples Campaign action in which we took part (see report at Cassie Dickman, “Protestors of Christopher Columbus ‘Genocide’ Climb Statue, Get Arrested at California Capitol,” The Sacramento Bee, June 5, 2018, https://www.sacbee.com/news/politics-government/article212594239.html).

This photograph of eight-year-old Cree boy Thomas Moore Keesick before and after his enrollment in Regina Indian Residential School, Saskatchewan, is found, with helpful analysis, at “How Did Residential Schools Impact Native Canadians?,” CHC2D Candian History, Unit 1: 1914–1929, https://sites.google.com/a/hdsb.ca/gwss-chc2d/unit-1-1914-1929/7-how-did-residential-schools-impact-native-canadians.

Paul leaves Iconium (Acts 13:51) and later Corinth (18:6) in such fashion, though note that the same gesture is used against him by his Jerusalem opponents (21:23).

In Genesis 19, the Sodomites refuse and then abuse the very angels that Abraham and Sarah had welcomed in Genesis 18.

Roger Epp, in the title essay of his collection We Are All Treaty People: Prairie Essays (Edmonton: University of Alberta Press, 2008), 133, quotes James Tully, “A Just Relationship between Aboriginal and Non-Aboriginal Peoples of Canada,” in Aboriginal Rights and Self-Government, eds. Curtis Cook and Juan Lindau (Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2000), 59.

Epp, We Are All Treaty People, 133.